ng as in Inger & Young Shin

Among all the first and last names of our SCEP tutors this year, only two feature the velar nasal /ŋ/, and these belong to our visitors from overseas, Inger Mees and Young Shin Kim.

Among all the first and last names of our SCEP tutors this year, only two feature the velar nasal /ŋ/, and these belong to our visitors from overseas, Inger Mees and Young Shin Kim.

Inger comes to us from Denmark, and tells me that in Danish her name is phonemicized as /ˈeŋə/. The first vowel in Danish sounds rather like the English KIT vowel /ɪ/, which is handy as that’s the vowel English speakers will readily choose on the basis of the spelling:

(The final -r is unpronounced in Denmark, just as in England; see SCEPLog 5.)

Young Shin (영신) comes from Korea; the first syllable of her name, which can also be spelled Yeong, sounds in Korean rather like English young, /jʌŋ/:

(English shin /ʃɪn/ is a less close match for the second syllable in Korean.)

In English as in Danish and Korean, /ŋ/ is a fully-fledged phoneme which can appear without a following /k/ or /g/. This can be tricky for some non-natives to pronounce, especially when a vowel follows, as in lo/ŋ/ago or goi/ŋ/out.

There’s a general rule in English that /ŋ/ doesn’t appear before a vowel which is in the same morpheme (word-part). So finger, a single morpheme, is /ˈfɪŋgə/, while singer, made up of two morphemes, sing + er, is /ˈsɪŋə/. However, there are exceptions like hangar which is commonly pronounced /ˈhæŋə/ despite being a single morpheme. So a name like Inger might go either way. In my recording above, I said /ˈɪŋə/, approximating Inger’s own pronunciation.

Note that if we say Young Shin’s full name, Young Shin Kim, the /n/ of Shin may assimilate to the /k/ of Kim, giving Young Shi/ŋ/Kim:

Unaspirated Scott

Day 7 of the UCL Summer Course in English Phonetics brings the first of our lectures on intonational meaning from Kate Scott of Kingston University. Both of Kate’s names contain voiceless velar plosives, but they’re interestingly different. We’ve seen already that the sounds /p t k/ are aspirated at the beginning of a word or stressed syllable, as in [kʰ]ate:

Day 7 of the UCL Summer Course in English Phonetics brings the first of our lectures on intonational meaning from Kate Scott of Kingston University. Both of Kate’s names contain voiceless velar plosives, but they’re interestingly different. We’ve seen already that the sounds /p t k/ are aspirated at the beginning of a word or stressed syllable, as in [kʰ]ate:

But this doesn’t happen if the plosive is immediately preceded by /s/ in the same word or syllable, as in Scott:

In fact, the resulting unaspirated plosive sounds very like English /g/, so that this name sounds more like /s/ + got than like /s/ + cot. Here is Scott again, followed by the same recording but with a gap inserted between the /s/ and the rest:

This comes as something of a shock to many people. But for confirmation, here is the word speech from both the Oxford and Cambridge online dictionaries, followed by the same recordings with /s/ removed – which sounds like beach:

You might wonder why dictionaries don’t transcribe words like Scott and speech as /sgɒt/ and /sbiːtʃ/ rather than /skɒt/ and /spiːtʃ/. This is a possibility in theory, but in practice would lead some non-natives into pronunciations with too much voicing. As things stand, many non-natives who have learned to aspirate the initial plosives in words like cot and peach carry this over into words like Scott and speech, resulting in non-native pronunciations like [skʰ]ott:

So, if you’ve been pronouncing SCEP with aspiration, as [skʰ]EP, try saying it without!

SCEPlog 1 Postalveolar Jane SCEPlog 2 Aspirational Paul

SCEPlog 3 Sam /v/ictor /w/ood SCEPlog 4 Bob Ladd

SCEPlog 5 Non-rhotic Margaret SCEPlog 6 Devoiced Cris

SCEPlog 7 Unaspirated Scott SCEPlog 8 ‘ng’ as in Inger & Young Shin

Devoiced Cris

Already it’s week 2 of UCL’s Summer Course in English Phonetics, and we can go into a bit more detail on points we covered in week 1.

Already it’s week 2 of UCL’s Summer Course in English Phonetics, and we can go into a bit more detail on points we covered in week 1.

Last week I used the name of Paul Carley to discuss the aspiration of the English voiceless plosives /p t k/, as in [kʰ]arley. (The square brackets indicate that we’re showing finer detail than in ‘phonemic’ dictionary transcription.)

Now we can turn to our tutor Cris Chatterjee, whose first name begins with the consonant cluster /kr/:

As in [kʰ]arley, the /k/ is followed by an extended voiceless period before voicing starts (or ‘positive voice onset time’). This means that a good part of the /r/ is devoiced, which we transcribe phonetically with the symbol [ ̥] as in [kɹ̥ɪs]. (The rotated [ɹ] is the postalveolar kind of /r/ that occurs in English; it’s normally an approximant but here quite fricative.) You can hear the devoicing if I extend the [ɹ̥] in Cris:

And here is the [kɹ̥] portion alone:

The approximants /w r l j/ undergo some degree of devoicing whenever they occur after /p t k/ at the start of a word or stressed syllable, eg twin, queue, apply. Although we transcribe devoicing with a different symbol from the aspiration mark [ʰ] used before vowels, the phenomenon – delayed onset of voicing – is essentially the same.

SCEPlog 1 Postalveolar Jane SCEPlog 2 Aspirational Paul

SCEPlog 3 Sam /v/ictor /w/ood SCEPlog 4 Bob Ladd

SCEPlog 5 Non-rhotic Margaret SCEPlog 6 Devoiced Cris

SCEPlog 7 Unaspirated Scott SCEPlog 8 ‘ng’ as in Inger & Young Shin

Non-rhotic Margaret

Day 5 of the UCL Summer Course in English Phonetics brings an afternoon lecture by Margaret Miller comparing the sound systems of English and Spanish. I encourage all SCEP participants to attend, because we learn so much about pronunciation by comparing languages. (Next week we have a lecture from Toyomi Takahashi comparing English and Japanese; SCEP is certainly not about studying English Phonetics in isolation.)

Day 5 of the UCL Summer Course in English Phonetics brings an afternoon lecture by Margaret Miller comparing the sound systems of English and Spanish. I encourage all SCEP participants to attend, because we learn so much about pronunciation by comparing languages. (Next week we have a lecture from Toyomi Takahashi comparing English and Japanese; SCEP is certainly not about studying English Phonetics in isolation.)

Yesterday’s Quiz Question was: In the name Margaret Miller, the letter r occurs three times, but only one of the three r‘s must be pronounced – which one, and why?

The answer is: the second letter r must be pronounced, because it’s immediately followed by a vowel. SSB is a non-rhotic variety of English in which the sound /r/ is pronounced only before a vowel. So we can transcribe Margaret’s name as /ˈmɑːgrət ˈmɪlə/, with only one /r/ pronounced:

If Miller is followed directly by a vowel, as in Margaret Miller appeared, then r-liaison may occur, with the pronunciation of a linking r:

(I wrote a substantial blog post about linking r, here. It includes lots of audio illustrations of linking r occurring when there is no r in the spelling.)

SCEPlog 1 Postalveolar Jane SCEPlog 2 Aspirational Paul

SCEPlog 3 Sam /v/ictor /w/ood SCEPlog 4 Bob Ladd

SCEPlog 5 Non-rhotic Margaret SCEPlog 6 Devoiced Cris

SCEPlog 7 Unaspirated Scott SCEPlog 8 ‘ng’ as in Inger & Young Shin

Bob Ladd

Day 4 of the UCL Summer Course in English Phonetics brings our annual guest lecture. This year we’re delighted and honoured to welcome the world-famous intonation expert (and my good friend) Prof Bob Ladd. I might also say honored, because although Bob comes to us from Edinburgh in Scotland, he’s originally American.

Day 4 of the UCL Summer Course in English Phonetics brings our annual guest lecture. This year we’re delighted and honoured to welcome the world-famous intonation expert (and my good friend) Prof Bob Ladd. I might also say honored, because although Bob comes to us from Edinburgh in Scotland, he’s originally American.

The vowels in Bob’s names illustrate a couple of differences between BrE and AmE – one phonemic, one phonetic. In BrE (the Southern variety which we use as our reference on SCEP), Bob contains the short LOT phoneme, shown in EFL materials as /ɒ/:

This short vowel contrasts with the long PALM phoneme /ɑː/, so we can get contrasting pairs like bomb /bɒm/, balm /bɑːm/. AmE lacks a distinct LOT phoneme, so in AmE bomb is pronounced with the same vowel as balm. Check out these two words in the Merriam-Webster Learner’s dictionary of AmE and you’ll see they have the same transcription, /bɑːm/. Here’s Bob with this vowel:

Bob’s surname contains the TRAP phoneme in both BrE and AmE. But this same phoneme is phonetically different in the two accents. In AmE it tends to be [æ] (as it also was in the older British reference accent RP):

But in contemporary SSB it’s more like [a]:

This is why some resources like the Oxford English Dictionary and Gimson’s Pronunciation of English 8th Ed. have updated to /a/ as the BrE phoneme symbol.

And here’s a Quiz Question, to be answered in tomorrow’s SCEPLog: In the name of our tutor Margaret Miller, the letter r occurs three times, but only one of the three r‘s must be pronounced. Which one (and why)?

SCEPlog 1 Postalveolar Jane SCEPlog 2 Aspirational Paul

SCEPlog 3 Sam /v/ictor /w/ood SCEPlog 4 Bob Ladd

SCEPlog 5 Non-rhotic Margaret SCEPlog 6 Devoiced Cris

SCEPlog 7 Unaspirated Scott SCEPlog 8 ‘ng’ as in Inger & Young Shin

Sam /v/ictor /w/ood

Day 3 of the UCL Summer Course in English Phonetics brings a lecture for the first time on SCEP by globe-trotting EFL teacher and travel blogger Sam Wood.

Day 3 of the UCL Summer Course in English Phonetics brings a lecture for the first time on SCEP by globe-trotting EFL teacher and travel blogger Sam Wood.

Sam’s surname begins with /w/ and his middle name, Victor, with /v/. These two sounds can be problematic for non-natives whose L1 (mother tongue) lacks the contrast between them. I find this a good example of how powerful the influence of L1 is, because /w/ and /v/ are not very hard to make, and English spelling is pretty reliable in distinguishing them. /w/ and /v/ don’t even look alike. This is /w/: and this is /v/:

and this is /v/: Anyone with lips and teeth can make those gestures.

Anyone with lips and teeth can make those gestures.

(I should point out before he sues that those pictures are of me, not Sam.)

English /w/ is a semivowel approximant, like a short version of an ‘u’ or ‘o’ vowel (‘o’ is a better reference for speakers of Japanese, which has a rather unusual ‘u’ vowel). The lips are pushed forward and the tongue is pulled back, as when you whistle your lowest-pitched note. English /v/ on the other hand is a fricative, made with more friction noise than many non-natives produce. Here are Wood and Victor, followed by their initial sounds:

SCEPlog 1 Postalveolar Jane SCEPlog 2 Aspirational Paul

SCEPlog 3 Sam /v/ictor /w/ood SCEPlog 4 Bob Ladd

SCEPlog 5 Non-rhotic Margaret SCEPlog 6 Devoiced Cris

SCEPlog 7 Unaspirated Scott SCEPlog 8 ‘ng’ as in Inger & Young Shin

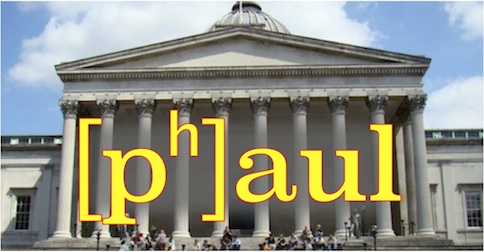

Aspirational Paul

Day 2 of the UCL Summer Course in English Phonetics brings the first of several lectures by Paul Carley of the University of Bedfordshire. Paul is the only SCEP tutor whose names both begin with plosive sounds. In fact they’re both voiceless/fortis plosives, which in English means they’re aspirated.

Day 2 of the UCL Summer Course in English Phonetics brings the first of several lectures by Paul Carley of the University of Bedfordshire. Paul is the only SCEP tutor whose names both begin with plosive sounds. In fact they’re both voiceless/fortis plosives, which in English means they’re aspirated.

In phonetic transcription these plosives are [pʰ] and [kʰ], though the aspiration is generally not indicated in the broad transcription of dictionaries.

I made a video about aspiration which you can see here, and there’s a version with Japanese subtitles here.

Aspiration, like /h/, can be thought of as a whispered version of the following vowel. You can hear this if I exaggerate the aspiration on Paul’s name:

and then isolate the aspirated plosives:

The different qualities of the following vowels (/ɔː/ and /ɑː/ in typical dictionary symbols) are audible in the two whisper-like bursts of aspiration.

Paul’s surname, like mine, ends in what some people call the ‘happY vowel’. For some years British dictionaries have transcribed this with /i/, a symbol which causes quite a bit of confusion as it isn’t a genuine phoneme of English. It’s best thought of as the form of the long FLEECE vowel which appears in the weakest (least stressed) syllables. (Paul and I agree that it might be better to transcribe it simply with the same symbol as any other FLEECE vowel – in typical dictionary transcription, /iː/.)

SCEPlog 1 Postalveolar Jane SCEPlog 2 Aspirational Paul

SCEPlog 3 Sam /v/ictor /w/ood SCEPlog 4 Bob Ladd

SCEPlog 5 Non-rhotic Margaret SCEPlog 6 Devoiced Cris

SCEPlog 7 Unaspirated Scott SCEPlog 8 ‘ng’ as in Inger & Young Shin

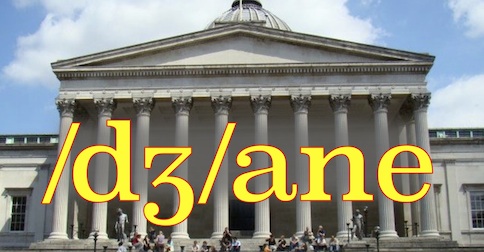

Postalveolar Jane

Today is the first day of UCL’s Summer Course in English Phonetics 2015! It’s my first year as Director of this internationally renowned two-week course, and a privilege for me to belong to a UCL line that stretches right back to Daniel Jones, the father of English Phonetics. This year we have nearly a hundred enrolled participants from around 20 countries.

Today is the first day of UCL’s Summer Course in English Phonetics 2015! It’s my first year as Director of this internationally renowned two-week course, and a privilege for me to belong to a UCL line that stretches right back to Daniel Jones, the father of English Phonetics. This year we have nearly a hundred enrolled participants from around 20 countries.

I’m joined by a wonderful team of tutors and lecturers, so I’m going to post a short daily piece on a feature of English Phonetics inspired by the names of our teaching staff.

Today, let’s look at /dʒ/, the most popular initial consonant among these names. It appears in Jane Setter, Professor at Reading University, who with me will be giving our first lectures this morning. We find it also in Joanna Przedlacka (my Associate Director), Josette Lesser, John Harris – and in John Wells, who’s graciously helping out as a guest tutor on Wednesday. Differently spelled, of course, it also appears in Geoff Lindsey.

/dʒ/ is a tricky sound for speakers of many languages. It’s a postalveolar sound, sometimes called palato-alveolar. This means that the tongue is further back than for /s/ and /z/, but like those sounds /dʒ/ has sibilance – or strident noise caused by grooving the tongue and shooting a jet of air at the back of the teeth. (This is why silbilants don’t sound right if you lose your teeth.)

Different tutors will have their own favourite ways of helping non-natives to make this sound; I find it helps to try and get the sound ‘shhh’ [ʃːːː] right first – it’s also postalveolar and has the lip rounding typical of these sounds. Just search for ‘shhh’ in Google Images and see what you get!

/dʒ/ is also voiced/lenis and an affricate. This means that, unlike /ʃ/, it has to begin with a full stoppage of the air coming from the lungs – which, after all, is why the IPA symbol /dʒ/ begins with a d.

SCEPlog 1 Postalveolar Jane SCEPlog 2 Aspirational Paul

SCEPlog 3 Sam /v/ictor /w/ood SCEPlog 4 Bob Ladd

SCEPlog 5 Non-rhotic Margaret SCEPlog 6 Devoiced Cris

SCEPlog 7 Unaspirated Scott SCEPlog 8 ‘ng’ as in Inger & Young Shin

Meet the fockus

On my recent teaching travels, I met as usual many impressive individuals who use English non-natively at the highest level. But I did encounter, from speakers with several language backgrounds, a pronunciation that really hits the ear of the native English speaker. This involves the very common word focus.

On my recent teaching travels, I met as usual many impressive individuals who use English non-natively at the highest level. But I did encounter, from speakers with several language backgrounds, a pronunciation that really hits the ear of the native English speaker. This involves the very common word focus.

Native English speakers pronounce the stressed first syllable with the long GOAT vowel, so that focus begins like folk. This is a general feature of two-syllable ‘ocus’ words. Here is folk followed by focus, locust, locus, hocus-pocus and crocus:

The problematic non-English pronunciation is one which makes the stressed vowel too short and/or too open in quality: too much like the LOT vowel, as in pocket, soccer, shocking and hockey:

Here, for comparison, is native focus followed by a problematic ‘fockus’:

The problem with using a LOT-type vowel in focus is that it makes the word sound uncomfortably like f*ck us (because LOT is more similar than GOAT to the STRUT vowel of f*ck). It was exactly this phonetic proximity that was exploited in the Hollywood comedies about the ‘Focker’ family, Meet the Parents, Meet the Fockers and Little Fockers. (The LOT vowel is somewhat different in Britain and America, but the joke – and the problem – is essentially the same on both sides of the Atlantic.) In order to avoid a restricted ‘R’ rating on these films, the producers had to prove to the Motion Picture Association of America that there really were people named Focker.

The word focus, of course, was not invented by the English-speaking world. It’s an international word – and that’s the ultimate cause of the problem. Whenever we speak foreign languages, international words tempt us to fall back on their pronunciation in our mother tongue. I always recommend trying to pronounce international words as they’re pronounced in the language you’re using.

Further notes

The GOAT and LOT vowels are commonly shown in BrE dictionaries as /əʊ/ (BrE) and /ɒ/, eg focus /ˈfəʊkəs/, pocket /ˈpɒkɪt/. The CUBE dictionary uses /əw/ and /ɔ/, eg focus /fə́wkəs/, pocket /pɔ́kɪt/. (/ɔ/ makes explicit the likeness to similar vowels of German, Italian, French, etc.) American GOAT and LOT are commonly shown as /oʊ/ and /ɑː/.

In familiar two-syllable words, the GOAT vowel is used when stressed ‘o’ is followed by a single ‘c’ in the spelling, eg focus, locust etc, and also local, vocal, Coca(-Cola), process, social, etc; while the LOT vowel is typically used when ‘o’ is followed by ‘ck’ or ‘cc’. Exceptions include the rare words jocund and socage, which are pronounced with LOT, as if they were written jockened and sockage.

Pronunciations to recognize

A few weeks ago I discussed the verbs recommend, represent, resurrect, recollect, reminisce. In these verbs, natives pronounce the re- with the ‘open e’ sound [ɛ] of red, dress, etc, so recommend begins like wreck. Non-natives often get this wrong by giving re– the more usual pronunciation of words like reaction.

A few weeks ago I discussed the verbs recommend, represent, resurrect, recollect, reminisce. In these verbs, natives pronounce the re- with the ‘open e’ sound [ɛ] of red, dress, etc, so recommend begins like wreck. Non-natives often get this wrong by giving re– the more usual pronunciation of words like reaction.

Those verbs all have the main stress on the last syllable: recomménd, represént, resurréct, recolléct, reminísce. I’d now like to draw your attention to verbs which are similar except that they have the main stress on the first syllable.

Key examples are récognize and réconcile. Again, non-natives often get these wrong, not realizing that in native speech they begin like wreck:

There’s a fairly small number of such 3-syllable verbs beginning [rɛ́]. Half a dozen of them end in -ate: rénovate, réplicate, résonate, rémonstrate, rélegate, régulate.

To these we can add réctify and a few words which are both nouns and verbs, eg réprimand, rémedy, régister, régiment:

Further notes

In English regiment has a different final vowel depending on whether it’s a noun or a verb: the verb has mɛnt, but the noun has the little colourless vowel schwa, mənt.

Historically, all the above words except regulate, regiment and rectify contain the Latin prefix re- meaning ‘back’ or ‘again’. John Wells wrote a detailed blog post about the prefix re- in English, here.

As Alex Rotatori reminds us (in the comments below), the last syllable of reprimand has the long PALM/START vowel in Standard Southern British. In the clip above I use the TRAP vowel, the historically older form, still used in Northern England and North America, and which is an acceptable alternative standard form. Here’s the SSB version: