How to say kudos and Bezos

Kudos to Amazon’s founder Jeff Bezos for becoming, according to Forbes magazine, the world’s third richest person.

Kudos to Amazon’s founder Jeff Bezos for becoming, according to Forbes magazine, the world’s third richest person.

The pronunciation of his family name, which comes from his Cuban stepfather, is not straightforward for English speakers, on either side of the Atlantic. Here’s how he says it himself:

In the first syllable of Bezos he uses his FACE vowel, as in baby and basic, and in the second syllable he uses his GOAT vowel, as in zodiac and Amazonian. (The American GOAT vowel is often transcribed as /oʊ/, but like many Americans Mr Bezos pronounces it with quite a ‘fronted’ vowel.)

Americans commonly pronounce the ending -os with the GOAT vowel, in words like cosmos, Carlos and Barbados. And they’re consistent in choosing this vowel for Bezos. However they’re not so sure about the e in the first syllable – most use FACE, as Mr Bezos himself does, but others use FLEECE (as in Zambezi) or DRESS (as in embezzle):

Brits, on the other hand, practically never use their GOAT vowel in the ending -os. In words like cosmos, Carlos and Barbados, they use their short LOT vowel (usually transcribed /ɒ/), as in boss and across. Unsurprisingly, some of them use this vowel in Bezos too:

But Bezos is a rare name, quite unknown to most Brits until they heard Americans talking about the founder of Amazon. And so, very unusually, some Brits copy the American pronunciation and pronounce this particular -os with their GOAT vowel:

Kudos, used as expression of congratulations or respect, comes like cosmos from Ancient Greek, where it meant ‘glory’. As expected, Brits pronounce the -os of kudos like the -os of cosmos, with their LOT vowel:

(Brits typically pronounce the first syllable like queue.)

But something odd has happened to this word in American English. For many Americans, kudos doesn’t follow the pattern of cosmos, Carlos, Barbados and Bezos. Rather, it’s been reanalysed as a plural, perhaps by analogy with congratulations. This means that the final s is pronounced as a z, as in photos and commandos:

The plural use of kudos is illustrated by these phrases:

And it can even be heard turned into a countable singular, without the ‘plural’ -s ending:

Not all Americans treat kudos as a plural. Some give it the same final s as cosmos and Bezos:

But it can still be treated as a countable singular, with an indefinite article:

whereas kudos is uncountable in British English, roughly equivalent to ‘respect’. In the US it’s even possible to hear kudos used as a countable singular, but pronounced with a final z like a plural:

So

A new use of the word so has arisen. Traditionally, so introduces an idea which follows from what precedes. Definitions in Oxford Dictionaries include ‘therefore’, ‘and for this reason’, ‘with the result that’. For example, I sometimes use so to begin the last paragraph of my posts – introducing a conclusion which follows from the facts I’ve presented:

A new use of the word so has arisen. Traditionally, so introduces an idea which follows from what precedes. Definitions in Oxford Dictionaries include ‘therefore’, ‘and for this reason’, ‘with the result that’. For example, I sometimes use so to begin the last paragraph of my posts – introducing a conclusion which follows from the facts I’ve presented:

But in a newly fashionable use, so introduces answers to questions. More widespread in the US but rapidly catching on in Britain, it’s particularly noticeable in TV and radio interviews. A couple of British examples:

A: So this is a political game.

A: So, there were elements of this that I really did love.

Before this fashion arose, such speakers may have introduced their answers with well instead. Well is described by dictionaries as ‘used to begin a story or explanation’ (Merriam-Webster) or ‘to show that we are thinking about the question that we have been asked’ (Cambridge).

Question-answering well is slightly informal: it has an air of improvisation, sometimes indicating that the speaker is thinking up an answer on the spot,  rather than knowing the answer already. But so, as we’ve seen, is associated with conclusions that follow from known evidence – which suggests not improvisation but rather command of the facts.

rather than knowing the answer already. But so, as we’ve seen, is associated with conclusions that follow from known evidence – which suggests not improvisation but rather command of the facts.

It’s perhaps unsurprising, then, to hear this new, question-answering so in formal settings, from speakers of seniority. Here is Janet Yellen (69), Chair of the US Federal Reserve, described as the most powerful woman in the world, testifying before Congress:

breaks to the families of the top one percent?

A: So, I’ve indicated that I share your concern

resolved in an orderly fashion?

A: So, the living will process is something that’s

intended to be iterative

A: So, I’m not sure if that’s true

in which incredible economic and political power

now rest with the billionaire class?

A: So, all of the statistics that you’ve cited are ones

that greatly concern me

So, will so replace well?

So, I don’t know.

Further notes

It seems that the question-answering so is more often followed by a pause or intonation break than the traditional ‘therefore’ use. Even with its less improvisatory air, it clearly can be used (like well) to buy time.

Erdoğan: the herd’s verdict

The name Erdoğan raises several questions for speakers of English. One concerns the unfamiliar Turkish letter ğ; this is readily converted into English w. But the vowels are more problematic. Here I’ll discuss the stressed initial vowel.

The name Erdoğan raises several questions for speakers of English. One concerns the unfamiliar Turkish letter ğ; this is readily converted into English w. But the vowels are more problematic. Here I’ll discuss the stressed initial vowel.

In most languages, the spelling er corresponds, logically enough, to some kind of ‘e’ vowel followed by some kind of ‘r’ consonant. In Turkish, the vowel is a relatively open ɛ (leaning towards æ for some speakers):

The nearest English equivalent would be the pronunciation of the word air (ɛr in America, ɛː in southern Britain).

But in English words, the spelling er before a consonant is generally pronounced as the NURSE vowel: a long schwa əː in southern Britain, and an r-coloured vowel ə˞ in America. There are hundreds of examples, eg:

herd, verdict, term, perfect, person, service, alert, advert, commercial, convert, university, observe, reverse, Sherlock, Mersey, Germany

If a foreign name is only rarely used, its pronunciation may vary considerably. But if it becomes frequently used, a consensus generally emerges. For example, English speakers generally opt for their ‘air’ = SQUARE pronunciation in Camembert, their ‘er’ = NURSE pronunciation in Lucerne.

The weekend’s events have put Turkey’s president on everyone’s lips. So what are we hearing on British TV?

Occasionally we get the ‘air’ = SQUARE pronunciation:

But the herd’s majority verdict seems to be the ‘er’ = NURSE version:

This choice, between a generally more accurate SQUARE type pronunciation and a more English NURSE type pronunciation, arises with various foreign names, including Merkel and Berlusconi.

Further notes

Regarding the final vowel of Erdoğan, the most accurate English choice would be the PALM vowel, as in Botswana. This is the option chosen by Americans. Although some Brits use PALM, we can hear in the clips above that their majority choice is the TRAP vowel. This difference between American PALM and British TRAP often arises in foreign names, eg Ghandi, Vietnam, Sri Lanka, Milan.

However, the British choice of TRAP in Erdoğan is rather unusual, in that English words containing a after the sound w are generally pronounced with the vowel of LOT. Examples:

want, wand, watch, wash, wasp, wallet, waffle, swan, swallow, swap, quantity, qualification, squad, squash, squander, Watson, Wanda, Obi-Wan

Perhaps that exotic letter ğ somehow interferes with the influence of the w on the following a.

(The w generalization is blocked if the following sound is ‘velar’, k, g or ŋ, in which case the vowel of TRAP is used: wax, wag, quack, swagger, wangle, Swank, etc. There’s a small number of other exceptions, such as the onomatopoeic word wham and the name David Walliams.)

Game of Throwns

Everyone seems to be talking about the TV series Game of Thrones. I haven’t seen any of it, and don’t feel much inclined to, after all the spoilers I’ve been exposed to in social media and overheard train conversations. I did however watch two marvellous series about this country’s real-life game of thrones, Prof. Robert Bartlett’s The Normans and The Plantagenets.

Everyone seems to be talking about the TV series Game of Thrones. I haven’t seen any of it, and don’t feel much inclined to, after all the spoilers I’ve been exposed to in social media and overheard train conversations. I did however watch two marvellous series about this country’s real-life game of thrones, Prof. Robert Bartlett’s The Normans and The Plantagenets.

An interesting feature of Prof. Bartlett’s speech is that he pronounces past participles like grown, known, shown as two syllables: /ˈgrəwən, ˈnəwən, ˈʃəwən/. This brings such words (back) into line with -en participles like broken, stolen, chosen. (Compare Middle English knowen, Old English cnāwen.)

So pairs like throne and thrown, identical for most of us, are differentiated: respectively, /θrəwn/ and /ˈθrəwən/. Here is Prof. Bartlett saying She’s shown kneeling:

And known as ‘misericords’:

He’s not unique. Just this week, the success of Wales in another historic game of conquest, Euro 2016, was celebrated by BBC Sports Editor Dan Roan with the words the togetherness this remarkable team has shown:

in which shown is pronounced as a rhyme with his surname: /ˈʃəwən/ and /ˈrəwən/.

I emailed Prof. Bartlett at the University of St. Andrews to ask about this feature, and he replied (with permission to quote):

I don’t think my pronunciation of “known” can be regional since my brother mocks it and we are both from South London.

Perhaps it is an unknown known.

Dan Roan, meanwhile, is from Northampton in the East Midlands.

I’m only aware of one accent in which this feature has been much discussed, namely that of New Zealand. Here’s New Zealand film director Sir Peter Jackson (Lord of the Rings, The Hobbit) saying the unknown thing with /ʌnˈnəwən/:

Perhaps, instead of telling me about Game of Thrones, somebody could enlighten me about the distribution of /ˈθrəwən/s.

Breksit, Bregzit

There can’t be many words which have gone from non-existence to omnipresence as quickly as Brexit.

There can’t be many words which have gone from non-existence to omnipresence as quickly as Brexit.

People are divided not only on how they feel about Britain’s departure from the EU, but also on how they pronounce this word. Brits generally pronounce the x as /ks/:

but many Americans pronounce it /gz/:

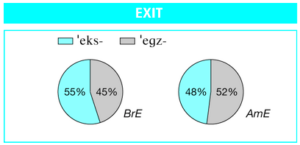

This difference reflects the two pronunciations of the word exit (both noun and verb) which predominate on either side of the Atlantic. We can see the difference in a preference poll which John Wells took some years back for his Longman Pronunciation Dictionary: It’s my impression that the UK-US divergence has if anything become more marked. Certainly we can find American dictionaries which prioritize /gz/, eg Merriam-Webster:

It’s my impression that the UK-US divergence has if anything become more marked. Certainly we can find American dictionaries which prioritize /gz/, eg Merriam-Webster: and British dictionaries which list only /ks/, eg Macmillan:

and British dictionaries which list only /ks/, eg Macmillan:![]() Here anyway are some Brits with /ks/:

Here anyway are some Brits with /ks/:

and some Americans with /gz/:

The /ks/ pronunciation is consistent with a generalization in English regarding ex- and stress: if the e is more strongly stressed than the following vowel we get /ks/, if the reverse we get /gz/. Common examples of /ks/ after stress are:

é/ks/ercise, dyslé/ks/ia, flé/ks/ible, hé/ks/agon, lé/ks/icon, sé/ks/y, É/ks/eter, Mé/ks/ico, Té/ks/as

And examples of /gz/ before stress are:

e/gz/áct, e/gz/ággerate, e/gz/ámple, e/gz/écutive, e/gz/háust, e/gz/híbit, e/gz/íst, e/gz/ótic, Ale/gz/ánder

(The /gz/ pronunciations can survive even when a more strongly stressed suffix is added, eg e/gz/ist-éntial.)

So pronouncing éxit and Bréxit with /gz/ goes against the stress generalization. Perhaps it’s an American declaration of independence.

Further notes

Other exceptions to the stress generalization are those words written with exc. These are pronounced with /ks/ regardless of stress, eg éxcellent, excéption.

Snap! Something went wrong

If you’re a user of Google’s Chrome web browser, you may have encountered a message beginning Aw, Snap! Something went wrong… when the browser is unable to display a page.

If you’re a user of Google’s Chrome web browser, you may have encountered a message beginning Aw, Snap! Something went wrong… when the browser is unable to display a page.

This took me by surprise when I first saw it. It’s not a use of snap! that’s found here in Britain, and I have no memory of it from my years living in America. Brits use this exclamation to register that the speaker and hearer have something in common, eg Snap, that’s the same phone as I’ve got or Snap, that’s exactly what happened to me.

This British use comes from a simple card game Snap, which most Brits learn as children. Players in turn reveal their cards and, when two successive cards have the same face value (eg two sixes), the first player who shouts Snap! wins all the revealed cards. The game is explained in more detail in this video (phonetics fans will notice that its presenter has labial r, TH-fronting and L-vocalization):

By contrast, the American use of the word, often preceded by aw or oh, is basically a euphemism (an inoffensive alternative) which replaces expletives like damn and sh*t. It’s typically a reaction when something bad happens. Here are some Americans using it:

and one speaker expanding it to snappadiddly:

As far as I can establish, this use seems to have originated in African American English and to have become mainstream relatively recently. I think it’ll have to be used more widely than in Google Chrome before Brits adopt it.

Euroscepticism

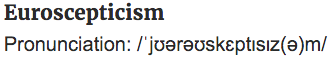

Every weekday I tweet (via @CUBEwords) a topical word from the day’s news, with phonetic transcriptions from the CUBE dictionary. This week I was about to tweet Euroscepticism when I hesitated, unsure about the location of the word’s main stress.

Every weekday I tweet (via @CUBEwords) a topical word from the day’s news, with phonetic transcriptions from the CUBE dictionary. This week I was about to tweet Euroscepticism when I hesitated, unsure about the location of the word’s main stress.

My first instinct was to put it on Euro-, making EUroscepticism. I checked Oxford Dictionaries (not many other dictionaries contain it), and was reassured to find that its transcription agreed with me: However, Oxford’s accompanying audio clip puts the main stress on -scepticism, making EuroSCEPticism (there’s also a secondary stress on the first syllable):

However, Oxford’s accompanying audio clip puts the main stress on -scepticism, making EuroSCEPticism (there’s also a secondary stress on the first syllable):

The site Forvo.com, where users contribute their own pronunciations, has two recordings of the word, one by a Scot and one by an American, and they both give the main stress to -scepticism:

Now my confidence was shaken, so I consulted my Facebook friends, who unanimously agreed that the main stress is on -scepticism, not Euro-. I also asked them about a similar word with the same number of syllables, Eurocommunism; they were more willing to give this word early stress: EUrocommunism. By contrast, Oxford Dictionaries gives this word late stress: EuroCOmmunism!

Many English words have a first part which, like Euro-, comes originally from Greek, eg aero-, astro-, bio-, geo-, hypno-, meno-, micro-, neo-, neuro-, photo-, psycho-, techno-. The stressing of such words is complex but not random.

If the second part of the word (the ‘head’) is just one syllable, then the word generally has initial stress: MEnopause, NEonate, PHOtograph, PSYchopath, etc. But if the head has more than one syllable, the stress depends more on the meaning category to which the word belongs.

For instance, words for scholarly/technical disciplines/practices are generally late-stressed: bioCHEmistry, hypnoTHErapy, microecoNOmics, psychoPHYsics. The same applies to substances, like hydroCORtisone, and diseases, like microCEphaly. As expected, biotechNOlogy is late-stressed but, if the head is abbreviated to one syllable, it becomes early-stressed: BIotech.

In words where the head noun is not scholarly but common and ‘everyday’, the stress is generally early. Most such words are relatively recent coinages: BIofuel, Ecowarrior, EUrovision, LIposuction, MIcrobrewery, PHOtocopier, PSYchokiller, etc. Many have one-syllable heads and so would be early-stressed anyway: Astroturf, GAstropub, MIcrochip, MOnorail, PHOtoshop, etc.

I suspect that Euroscepticism and Eurocommunism are somewhat indeterminate because they’re torn between the late stress of the more scholarly, technical words and the early stress of the recent, more everyday coinages. It may also be that English speakers would rather not have the main stress six syllables from the end of a word.

Further notes

If Eurocommunism is more likely to be early-stressed than Euroscepticism, the explanation may be related to a distinction between what have been termed ‘ascriptive’ and ‘associative’ meanings. In early-stressed words, the first part often ascribes a property to the head noun: a microbrewery is small, a monorail is unitary, a biofuel is a fuel which is (or was) alive. This is rarely the case with the late-stressed words: microeconomics is not itself a tiny science, biochemistry is chemistry applied to living things, psychophysics deals with the relation between physical and mental phenomena. Eurocommunism is somewhat more ascriptive, referring to communism which is European. Euroscepticism is more associative, referring to scepticism about (the union of) Europe.

Of course, the stress on all the words discussed above can be shifted due to context, emphasis, etc. In this post I’m discussing the default stress patterns which are used in isolation.

Triumph of the curse child

It’s almost a year since I discussed here the announcement of the play Harry Potter and the Cursed Child. More specifically, I considered the possible pronunciations of the word cursed.

It’s almost a year since I discussed here the announcement of the play Harry Potter and the Cursed Child. More specifically, I considered the possible pronunciations of the word cursed.

The verb form cursed is pronounced as one syllable, rhyming with first and worst. But the adjective cursed may be given a more old-fashioned pronunciation in which -ed belongs to a second syllable, as in blurted and spurted. My post included a poll allowing readers to vote for the pronunciation they preferred. Nearly three-quarters opted for the two-syllable version.

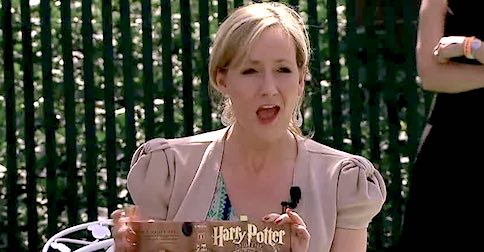

This week in London the first previews of the play took place, to an ecstatic response from fans. Harry Potter’s creator J. K. Rowling has asked audiences to keep the play’s secrets, but one cat is now out of the bag: the official pronunciation of cursed is one syllable.

I pointed out in my post and video that the final t of monosyllabic cursed may be lost before child, make it sound the same as curse. And curse child is exactly what we hear from J. K. Rowling herself:

And also from the play’s two producers, Sonia Friedman

and Colin Callender:

As I explained in my more recent post First class box sets, t may be lost whenever one word ends st and the next starts in a consonant, giving us many examples like firs’ class, las’ week, nex’ time, jus’ kidding, box’ sets, and now curs’ child.

A little training

The non-natives I work with sometimes use the plural trainings in their English. On the web it’s not hard to find this form being used in various languages:

The non-natives I work with sometimes use the plural trainings in their English. On the web it’s not hard to find this form being used in various languages:

Su partner global en Trainings de Management

Les trainings sont données dans plusieurs locaux a Paris centre

I trainings hanno l’obiettivo di condividere conoscenze

Trainings für Teamentwicklung und Kommunikation

But for most native speakers of English, training is an uncountable noun. The Cambridge online dictionary defines it as ‘the process of learning the skills you need to do a particular job or activity’ (my emphasis). This makes it less likely to be used as a plural.

For a countable unit of training, English prefers such compound nouns as training course, training day or training session:

So the phrase a little training, used by a native speaker, would mean ‘some training’ and not ‘a small-scale training course/session’.

Further notes

Actually, there are quite a lot of instances on the web of trainings used by natives. The majority seem to be from those who offer such ‘trainings’ professionally; a substantial proportion are in the area of ‘new age’ practice/therapy. Among the general population, however, I think it’s fair to say that training is uncountable.

The face of ancient Cambridge

Students of English soon learn that the letter a often has a pronunciation different from that in other languages. Examples are the English name of the letter A, and words like baby, name, latest and face. Phoneticians often refer to it as the FACE vowel. Its Standard Southern British pronunciation can be transcribed ɛj or ɛi, and is notated in many sources as /eɪ/.

Students of English soon learn that the letter a often has a pronunciation different from that in other languages. Examples are the English name of the letter A, and words like baby, name, latest and face. Phoneticians often refer to it as the FACE vowel. Its Standard Southern British pronunciation can be transcribed ɛj or ɛi, and is notated in many sources as /eɪ/.

The circumstances under which a has this pronunciation are rather complex, but here I want to mention two words which are widely mispronounced, ancient and Cambridge. These both have the FACE vowel, despite the fact that other words with the spellings anci and ambr do not. Words with anci include financial, rancid, dancing, fanciful. Words with ambr include Ambrose, ambrosia, Alhambra, Cambrian.

Here are native speakers demonstrating the FACE vowel in ancient:

and in Cambridge (the first syllable of which is like came):

Note that the River Cam on which Cambridge lies is pronounced more straightforwardly, with the short TRAP vowel, as in camera and camp:

(Cambric, a rather old-fashioned word for a type of cotton cloth, is supposed to have a pronunciation with the FACE vowel, but now seems more likely to be pronounced with the short TRAP vowel. The same applies to the geological world Cambrian.)