The demise of eə as in SQUARE

I recently spoke with a young person from abroad who had been studying postgraduate phonetics at an English university. As we chatted, I couldn’t stop myself trying to list the characteristics which together made up his strong foreign accent. Quite high on the list was the SQUARE vowel pronounced as eə. Despite his being a phonetician, and despite his having lived for years among native speakers who use the contemporary ɛː, he’d kept the old RP diphthong which I imagine had been taught to him by non-native schoolteachers, and which continues to be transcribed as such in textbooks and dictionaries.

I recently spoke with a young person from abroad who had been studying postgraduate phonetics at an English university. As we chatted, I couldn’t stop myself trying to list the characteristics which together made up his strong foreign accent. Quite high on the list was the SQUARE vowel pronounced as eə. Despite his being a phonetician, and despite his having lived for years among native speakers who use the contemporary ɛː, he’d kept the old RP diphthong which I imagine had been taught to him by non-native schoolteachers, and which continues to be transcribed as such in textbooks and dictionaries.

I don’t of course have a recording of this speaker, but here is a parallel example that recently caught my ear, from the celebrity language teacher Michel Thomas. Thomas was born in Łódź, Poland in 1914 and died in 2005. He was fluent in a number of languages but his English had a thick, and to my ear charming, foreign accent. Here he is teaching Italian, and using eə in prepare:

This kind of pronunciation hasn’t been common in the more prestigious kinds of native British English for a long time. Here is King George VI in 1948, saying “It gives me much pleasure to declare the Kingston power station open.” His declare with eə sounds very old-fashioned to native ears today:

The change in SQUARE was described by Clive Upton of Leeds University in a programme broadcast yesterday by BBC Radio 4 (it focused on the pronunciation of the Queen):

I have to confess that my heart sank as he attributed monophthongal ɛː to “younger people”. For many of Radio 4’s traditional listeners, attributing a trait to “younger people” is liable to equate it with wearing your pants low enough to expose your rear. And some non-native listeners may have inferred that ɛː is a youthful fashion, not a recommendable standard pronunciation.

What is the age below which ɛː is used? Evidently over sixty, since it’s used by Jeremy Paxman (61), the presenter of BBC TV’s Newsnight – a speaker so conservative that he still has ʊə in poor:

(The phrase in the middle is heir to a baronetcy; the word heir is pronounced the same as air.)

Here he is again, saying if he becomes mayor with mɛː for mayor:

Of course, as I pointed out in my post on smoothing, centring diphthongs like eə are relatively well preserved in lower-class speech. This was exemplified in yesterday’s radio programme, when presenter Michael Rosen (65), who had told us “I talk Estuary English”, later asked Am I getting there? with ðeə for there:

But anyone who stayed with Radio 4 after the programme heard the SSB continuity announcer telling us about a following programme hosted by Eddie Mair, and pronouncing Mair as mɛː, just like Paxman’s mayor:

The factors of age and/or social class are illustrated by a pair of adverts currently playing on television. One is for the Belgravia Centre, which specializes in hɛː loss and scalp kɛː, the other is for BUPA keə homes for the elderly:

The eə pronunciation is now so old-fashioned that highly-trained actors are either unwilling or unable to use it even when playing period characters who would have had it. Here is the fictional Lady Mary from TV’s Downton Abbey, supposedly speaking during the First World War, a time when the real-life Daniel Jones was busy codifying the accent of her class as “Received Pronunciation”:

(That brief clip is a compendium of divergences from the old-fashioned RP of the dictionaries: no eə, no ɪə, no ʊə, no æ, no ʌ, no uː, etc.)

John Wells (ageless) discusses here his decision to preserve the old eə in his dictionary transcriptions:

People do increasingly use a long monophthong for this vowel, rather than the schwa-tending diphthong implied by the standard symbol. What used to be a local-accent feature has become part of the mainstream. There are millions of English people, however, who still use a diphthong. To produce the distinction in pairs such as shed — shared EFL learners generally find it easier to make the square vowel diphthongal ([eə]) rather than to rely on length alone.

On the first point, my view is that the millions of eə-users in the Estuary area are maybe not the best BrE model for foreign learners. It’ll be interesting to hear, over the coming years, what happens to higher-class ɛː and lower-class eə.

On the second point, there must be a lot of experience behind John’s argument about EFL learners. But I’m not persuaded. What about aural competence? Do we teach students to produce eə while warning them that what they’re more likely to hear from SSB natives is ɛː? Anyway, my students tend to be higher-level learners, and I can’t bring myself to teach them a vowel that’s too archaic for “younger people” like Jeremy Paxman, and makes foreigners sound foreigner still.

I think there are two aspects, maybe minor, that tend to be missed by those who flatly decla’ the diphthong to be dead.

Firstly, the definition of the accent, in particular whether you count speakers of what John Wells called adoptive RP (GB, SSBE…).

Secondly, that – I think – the monophthong that is undoubtedly widespread today often enough consists of two single vowels in terms of intontation, an autodiphthong ©, as it were, which isn’t the case with ɔ or o for older ʊə, even when these are long.

I wonder when eəin the mouth of an EFL learner will actually start to sound prole. Probably not that soon, especially if it doesn’t come with other low-prestige features.

[eə] is rather like tapped [ɾ]. Depending on the accompanying features, [ɾ] either sounds like old Noel Coward RP, or like Scouse, or Scottish, or foreign.

Downton Abbey: I was also struck by the fairly modern pronunciations of some of the actresses/actors.

To [ɛɛ] or not to [ɛɛ]. I teach English phonetics to university students whose mother tongue is mostly German and who are in their twenties. I learnt to say /eə/ and /ʊə/, but am aware that I can’t impose my ‘OAP pronunciation’ on them. So I convinced myself to say /ɔː/ in words like ‘poor’, but haven’t managed yet to switch to [ɛɛ] in ‘square’. So I feel like a split personality.

I think the centering diphthong pronunciations are very natural to German speakers because it is a common realization of /VV/ + /r/ in many varieties of German.

Your affirmation that “centring diphthongs are less natural and less stable” strikes me since I am speaking a Southern German variety that has featured stable centering diphthongs [iə], [yə] and [uə] for more than thousand years. But I guess you are right.

Thanks for reading and commenting. It’s a good point, though I believe most Germans lost those Middle High German diphthongs. Who knows, maybe somewhere there’s a forgotten enclave of the British Empire whose centring diphthongs will last a thousand years.

Prof. John Harris, who knows far more than I do about phonological variation and change, tells me he’s skeptical about anything being very stable in Germanic long-vowel systems (including English). However, it is true that very natural systems like Spanish vowels are amazingly stable through the centuries and across the continents. And, in the grand scheme of Southern British English, it does seem that the centring diphthongs are/were just a “halfway house” in the loss of final r and l.

Mach’s point about the realization of /r/ in German is a good one, though. The realization as a centering diphtong is the standard one even in middle Germany even on a modern theatre stage. For instance: http://www.schauspielfrankfurt.de/schwarzer_bereich/stuecke.php?SID=1000105 (bottom of the page). The older realization as [r] even after a vowel, though still recommended in one of the standard text books on stage speaking (“Der kleine Hey”), sounds very artificial today.

While I do recognize ‘square’ with [ɛɛ], I’d have to force myself consciously to not realize it as [eə]. I don’t see that changing any time soon, since most of my quotidian exposure to English is in talking with other EFL speakers living in the Frankfurt area, whose German isn’t good enough to hold a conversation at ease, although they have been living here (and been exposed to German phonology) for years. This is a rather common phenomenon here in Frankfurt, and I’m wondering whether there is such a thing as an “international English accent”.

When I attempt to speak German I do my best to reproduce its centring diphthongs; I try not to impose my British monophthongs. I understand that Germans might be tempted to use their schwer vowel when they say English SQUARE, but it’s wrong for two reasons in addition to the centring diphthong: 1. the German schwer vowel starts too high; 2. the quantity is wrong – even in old-fashioned RP, SQUARE is not a long vowel + schwa.

Germans would be better off using their short ɛ + r as a model for English. Here, from “Der kleine Hey” on YouTube, are Zwerchfell and Wort:

which aren’t very diphthongal. Here are the endings of the syllables Zwerch- and Wort, which don’t seem very rhotic but also don’t seem to end in [ɐ]:

And that is in very clear, demonstrative speech. I have a hunch that syllables like those may sometimes be monophthongs in conversational German. What do you think?

Regarding the international pronunciation of English, there is a huge literature on English as an Intenational Language and English as Lingua Franca. Jennifer Jenkins is well known for proposing a “lingua franca core” of features – which would include rhoticity rather than centring diphthongs. I certainly don’t believe that “Anglo-Saxon” native accents are superior; my posts are just to provide native-speaker data (and some analysis) for those who are interested.

Of course, between the so-called “Inner Circle” of Anglo-Saxons (and Celts) and the EFL world, there are very large numbers of English speakers in India, Nigeria, etc. Here are clips of Indian and Nigerian English which include the word hair. The Indian example has rhotic [heɾ], the Nigerian example has non-rhotic [hɛ]:

I can’t check my references right now. If I speak “Wort” in my “stage voice”, I produce it as [vɔʁt] (or maybe as [vɔχt], I’m not quite sure). Curiously, though, “führt” very clearly becomes [fʏɐt]. Not sure, what I’d be doing in informal speech in either case. A monophthong in “Wort” would strike me as highly regional and non-standard. However, I doubt that the first (non-accented) syllable in “verstehen” would be anything but [fɐ], except in the slowest, most formal speech.

What do you think about Lipman’s point about the vowel in “square” being an “autodiphthong”? Personally, I’d love to adopt a standard English accent, but I have a suspicion that my Korean, Finnish, French, Romanian, Italian etc. friends wouldn’t understand me, if I produced it like the [ɛː] in German “Käse”.

I’m rather more interested in what you hear people actually saying than in what the references say!

It isn’t really “curious” if you have clear diphthongs in words like führt and schwer but more robust uvularity in words like Wort. The former have front vowels, and it’s more of a stretch to get from a front vowel articulation to a uvular articulation; and syllable-final position is a weak position, so it’s not surprising that the consonant lenites to a vowel. In a word like Wort, the vowel is back, much closer to the uvular position, so the consonant is under less pressure to weaken.

The regionality of the monophthongal pronunciations doesn’t mean they don’t exist and aren’t interesting. It’s often the case that non-standard variants point to the future of the standard dialect.

I can’t comment on autodiphthongs until I hear some phonetic and/or phonological arguments in favour of them.

Regarding your last point, I presume that your international friends find old native speakers easier to understand than less old ones. Do you think London Underground should change its train announcements from Leicester Squ[ɛɛ], Edgw[ɛɛ] etc. to the old-fashioned pronunciations for the benefit of foreign tourists?

Regarding your last point: of course not! That’s not the point. Rather, I’m trying to understand the phenomenon with a view on how I, as an EFL user, should try to cope with it. If I aim for [eə], this becomes in many circumstances involuntarily something like [ɛɐ]. But if I would aim for [ɛː], that would for me be the vowel in “Käse”; and if there should happen to be a subtle yet important difference in intonation, it would be more difficult to reproduce and would inevitably get lost in many speaking situation. Meaning, I might exchange something that is known, understood and more or less tolerated as a German accent with something yet unheard.

With regard to uvularization, shouldn’t what you write also apply to /ɪr/ and /ʏr/? If I try “Gürtel” and “Wirt” — again, as if speaking on a stage –, I produce them both with an uvularization similar to “Wort”. dwds.de agrees with me on the latter: http://www.dwds.de/?qu=Wirt (link to audio in the top left box). I guess, in informal speech, I’d expect all of them, “Wort”, “Wirt” and “Gürtel”, to have a diphthong.

I don’t disagree with what you write on dialects.

I was only joking about the underground! What sort of subtle but important problem do you anticipate from using the Käse vowel in SQUARE? The only thing that occurs to me is that you might be less likely to use r-liaison (e.g. square inch) than if you have the Berg vowel as your model. As for something “yet unheard”, why not be bold and give it a try! As for differences between führt and Wirt (if I understand right), I’m well out of my area and perhaps shouldn’t venture any more suggestions!

My native language is Spanish and something similar happens to me. I pick /ɔː/ or /ʊə/ depending on the word (saying /pɔː/ and /pjʊə/ according to what modern dictionaries depict as preferable today) but I struggle to incorporate [ɛː] and erradicate [eə] because the same “modern” dictionaries are reluctant to keep up to date in this respect. Wells says that changes that can be inferred as a rule don’t need to be shown in pronunciation dictionaries, but I disagree. It’s difficult to be constantly reminding yourself that one symbol stands for another one. And in the second edition of his dictionary (LPD, copyright 2000, the one I’ve used since 2002) he didn’t even include a note in the introduction mentioning [ɛː]. So it’s no wonder I speak like an 80-year-old though I’m 28!

No, for the time being, the diphthongs are stable in German. The “zwerch-” above clearly has a diphthong, and the “wort” has a uvular fricative, which isn’t the default pronunciation. Monophthongs are strongly associated with certain Hessian dialects.

1. Many thanks for confirming that truly monophthongal pronunciations exist – exactly what I expected. I’d be really grateful for a reference/link to some audio data for the progressive Hessian dialects you mention.

2. My point about Zwerch– is that the diphthong is slight, and would be a better model for SQUARE than a really clear diphthong as in schwer.

3. There is certainly no phonetic uvular fricative in that pronunciation of Wort. Maybe there is some uvularization which is hard to distinguish from the vowel; and the speaker seems to be using expressive breathiness. The reason I included the extract of the word’s ending is because it sounds very like [ɔt], and certainly not like [ɔχt].

1. Well, the second part is the same, be it ə or ɐ, but the first is ɛ in zwerch- and eː in schwer. (Except for some Westphalian dialects of High German, which will have eːɐ in both.)

2. Really?! Could you ask the general public? I clearly hear a ʁ there. (χ would be Ripuarian.)

3. Here‘s a Hessian comedian. I only watched the first part, but there are examples everywhere. The striking feature is that there are no ex-r diphthongs nor compensatory lengthenings, even for those where the first part is further away from schwa etc., eg kurz [kʊts]. There are other dialects (some High German dialects on Low German ground) that have long monophthongs for some of the older diphthongs, but in non-regional colloquial German, they seem to be pretty stable.

Many thanks for the reference – sorry, but I think my spam blocker has deleted a link.

Not sure what you mean by “the second part”. What I said about the syllables Zwerch– and Wort was that they “aren’t very diphthongal”, they “don’t seem very rhotic”, and they “don’t seem to end in [ɐ]”. All three points (depending on your interpretation of the word very!) are true, although the second point is weak because uvular approximation doesn’t stand out much in the context of back vowels. The two syllables’ endings are phonetically very different, but of course one can analyze them as phonologically ending in the same thing: I’m certainly not claiming (I couldn’t, as a low-level amateur in German) that this Wort actually rhymes with Spott. I don’t know whether trained phoneticians with zero knowledge of German would transcribe this utterance as [vɔʁt]. If I were to read [vɔʁt] as a non-linguistic “nonsense dictation” for students, I’d make the [ʁ] stronger and clearer.

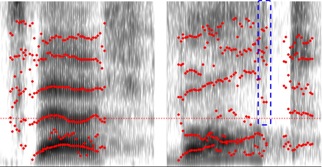

Just for interest, here’s a 0-6kHz spectrogram of the Zwerch– and Wort tokens. The diphthongal nature of the former is definite but small, mainly a downshift in F2 halfway through the vowel. This is followed by a big palatal fricative, heavily coloured by the preceding vowel’s formants. In Wort, the F1 and F2 region is roughly constant in frequency up to the [t], hence the heavy auditory [ɔ] colour (not [ɐ]) right up to the [t]. The vowel seems noisy throughout, and becomes noisier as it progresses. Just before the [t] there’s a brief increase in noise which I’ve highlighted with a dotted blue box, but it doesn’t correspond to much that’s audible (to me) and is nothing like the big [ç] in Zwerch-. Any r‘s here are weaker than the strong r‘s of rot and drohen and vowel-coloured by their “preceding” vowels. This is exactly the kind of thing which could lead (and apparently already has in some dialects) to true monophthongs.

Sorry to go on at such length!

Sorry for the confusion of the item numbers. By “second part” I meant the second part of the diphthongs in zwerch- and schwer in general, or in the pronunciation you’ll most likely meet in a German EFL learner. The first part is different, but the second part is more important when it’s about teaching the SQUARE vowel in English, isn’t it?

Thanks for the spectrograms and especially for the explanation – I haven’t much experience in acoustic phonetics. Still, in terms of auditory phonetics, I have no doubt. I’ve heard enough instances of [vɔʁt] [vɔχt] [vɔxt][vɔɾt][vɔrt] [vɔat] [vɔɐt] [vɔːt] [vɔt] and [voːat] (and others) not to be influenced by the spelling. 🙂

What I hear in the sample is voiced (ʁ), that might be why the spectrogram is less clear.

Here’s the link in plain text: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5aO7FeqNDsY

Again, many thanks. I’ll check out the link when I get the chance. (What I really want to understand is why your comments get caught by my spam blocker!)

Something puzzles me about Upton’s views on this. In the chapter in Urban Voices that he wrote with Widdowson and Stoddart, only ɛə is given for Sheffield’s SQUARE vowel. ɛ: is not mentioned. It strikes me as implausible that [ɛ:] had not become established in Sheffield by the ’90s. [ɛ:] is originally the Midlands pronunciation. Petyt (based on fieldwork done in 1970-1) found that it was spreading to West Yorkshire. It must have gone through Sheffield in the process.

My best guess is that Widdowson and Stoddart disagreed with Upton on how to represent the SQUARE vowel of RP, and they won by 2-1 majority.

Your best guess could be true. This is a good example of how fortunate we are today to have multimedia. Back in the 90s we were more dependent on printed symbols, which are merely an imperfect tool in capturing the reality of sound systems. The result is that you can’t be sure from that chapter whether the [ɛə] was real or the baggage of conservative R.P. But it shouldn’t be too hard to find real recordings of 90s Sheffield. Or email Clive.

My comments were too lengthy to give here.

They can be seen as my Blog 392 at http://www.yek.me.uk

I would never cut out the end of a diphthong to falsify the data. The real audio data is by far the most important thing about this blog.

Here are a couple of adverts I caught on the telly. One is for the Belgravia Centre, which specializes in hair loss and scalp care, the other is for BUPA care homes for the elderly. My students can choose whichever pronunciation they find more suitable as a model.

Your blog has been extremely useful! I’m preparing (with /ɛː/) a Phonetics I final, and I’ve had to update some of my knowledge, especially these monopthongisations and the lowering of /æ/. You manage to make phonetics really interesting. Thanks!

Thanks for your kind words, Victoria – much appreciated – and good luck for your final.