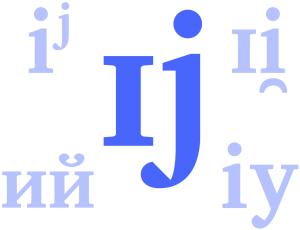

Seeing the FLEECE diphthong

When I teach groups, especially groups of students, they normally have to be encouraged to speak aloud. So it took me by surprise when, on several occasions in the past year, groups of my students simultaneously chanted aloud an example I was discussing, without my having asked them. This happened with separate groups of Italian and Japanese students. On each occasion, I was referring them to a page in their printed teaching materials; I pointed at the relevant example in my own copy and said, ‘Can you see it?’ Each time, they suddenly chanted the example. Each time, it took me by surprise.

When I teach groups, especially groups of students, they normally have to be encouraged to speak aloud. So it took me by surprise when, on several occasions in the past year, groups of my students simultaneously chanted aloud an example I was discussing, without my having asked them. This happened with separate groups of Italian and Japanese students. On each occasion, I was referring them to a page in their printed teaching materials; I pointed at the relevant example in my own copy and said, ‘Can you see it?’ Each time, they suddenly chanted the example. Each time, it took me by surprise.

They had misinterpreted my question as ‘Can you say it?’ Native English-speaking students would not have done this.

We’re all aware that non-natives speak differently from natives (regardless of the language). It’s a less obvious fact that non-natives hear differently. In general, non-natives simply don’t have native pronunciations in their minds. Italian and Japanese speakers don’t typically have in their minds the authentic English FLEECE vowel of see. Rather, they produce – and expect to hear – a vowel like their own ‘i’, pure and unchanging, ie a monophthong. But see it is sɪjɪt. When my students heard my FLEECE diphthong ɪj, they interpreted it as the FACE diphthong of say.

A contributing factor is the tendency of non-native FACE to be too close. If the FACE vowel is stored in your head as ej or ei, rather than as the native ɛj, then your productions and your perceptions may both confuse FACE and FLEECE. (This kind of production is demonstrated in my Phrase of the Week post where a Ukrainian speaker pronounces pain as uncomfortably like penis.)

The established type of transcription system can reinforce these problems. It encourages the non-native to believe that FLEECE is a monophthong, ‘/i:/’. Among the people I teach and coach, the majority of those who use dictionary transcriptions assume wrongly that these are phonetically accurate. Some are shocked when I point out that FLEECE’s diphthongal characteristics are not some revolutionary fantasy of mine but are well known among phoneticians. Here’s Henry Sweet’s A New English Grammar on FLEECE in 1900:

In the south of England it is diphthongized into (i) [by which Sweet means the KIT vowel] followed by very close (i), which is nearly the sound of the consonant (j) in you, so we write (sij), etc. (p. 232).

Here’s John Wells on FLEECE in Accents of English, 1982:

the general phonetic nature of this vowel could be adequately represented as /i/, as /iː/, or indeed as /ɪi/, /ɪj/ (p. 140)

and Gussenhoven & Broeders (English pronunciation for student teachers, 2nd ed., 1997):

RP /iː/, as in piece, sea, is a close, front, unrounded vowel. It is typically somewhat diphthongised, much like [ɪi] (p. 95)

Phonetically, the nucleus of the FLEECE diphthong varies in the [i-ɪ-e] region depending on speaker, speech rate and phonetic context. Like the other English diphthongs, it may be compressed into a monophthong in running speech. As an illustration of ɪj, here from the Oxford Learner’s Dictionary online is knee, nɪj:

And knit, nɪt:

Replacing the n and virtually all of the vowel of knit with the beginning of knee results in what is still an entirely acceptable knit:

Phonologically, FLEECE certainly belongs to the same class as FACE, PRICE and CHOICE. In terms of linking, FLEECE, FACE, PRICE and CHOICE connect to a following vowel with j (unless hard/glottal attack is chosen), eg key‿event, day‿out, buy‿anything, enjoy‿it. (I, like Henry Sweet, consider the j to be intrinsic to all four of these vowels. For further analysis see this post.)

In terms of phonotactics, FLEECE goes with FACE, PRICE and CHOICE (plus GOOSE, GOAT and MOUTH) to make up the class of English vowels which may occur before another vowel within a morpheme, eg museum, chaos, giant, voyage (ruin, oasis, power). By contrast, the set of ‘long monophthongs’ in the established transcription system (FLEECE, PALM/START, GOOSE, NURSE, THOUGHT/NORTH) do not constitute any natural class whatsoever.

(The CUBE dictionary which I co-edit has ɪj as a default for FLEECE, though ij is defensible, highlighting the diphthong’s change in sonority rather than a change in quality. CUBE allows the weak offglide to be shown either as j or as non-syllabic i̯.)

As with FLEECE, the established transcription of FACE can be misleading for non-natives, many of whom make it too close. In my experience, the majority of those who refer to dictionary transcriptions see the symbol ‘e’ and simply interpret it as the ‘e’ of their language. This applies not only to ‘/eɪ/’ for FACE but also to ‘/e/’ for DRESS. The result is non-native FACE which sounds too much like native FLEECE, and non-native DRESS which sounds too much like native KIT.

The following clip sounds like a native SSB English speaker saying ‘saw this’:

But it’s a Japanese speaker saying soo des, which means ‘that’s right’. This shows how similar Japanese e is to English KIT. I find that students and clients from many language backgrounds often sound more native if they can be persuaded to use their ‘e’ rather than their ‘i’ in KIT words. For DRESS, on the other hand, they typically need to be encouraged to make an opener vowel than they’re accustomed to; in this, the symbol ɛ can provide a bit of assistance. It’s always harder for me to persuade those clients who believe religiously in the established symbols /iː/, /ɪ/, /e/, /eɪ/.

The FLEECE-KIT contrast is notoriously hard to teach to all those whose mother tongue has only one close front vowel, i. These two English vowels differentiate many words, including famous pairs like sheet-sh*t, piece-p*ss, beach-b*tch. As I’ve just suggested, it can help many learners and users to coax them in the direction of their ‘e’ for KIT.

For FLEECE, I find it hard to use ‘length’ as a teaching tool with those whose mother tongue simply lacks a long-short contrast, like Spanish, Russian and French. But these three languages do contain both i and j. I find it can be effective to persuade such speakers that the FLEECE vowel has two parts, i followed by j. (Russian and French actually contain ij, written ий and ille, though not in the same range of phonetic contexts as English FLEECE.)

I find that sɪjing the FLEECE diphthong often makes things easier.

IMO, the phonemic symbols don’t matter that much. Either learners of English can imitate the sounds or they can’t. To use an example from French: transcribing roux as /ʁu/ doesn’t help me pronounce it any better than transcribing it /ru/. I think phonemically transcribing it /ru/ is fine (In fact, I think that transcription is fine for that word in English too, except you could put length marks after the “u” if you wanted to). The phonetic difference will be obvious to anyone with ears that work. That’s just my 2 cents.

Welcome Nicholas and thanks for commenting! There are many criteria for choosing phonemic symbols. The most established vowel symbols for BrE are those of Gimson (1962), which he selected to be “explicit on the phonetic level” (p. v). Ironically, many conservatives now cling to Gimson’s phonetically explicit (but no longer accurate) system on the grounds that phonemic transcription doesn’t have to be phonetically explicit!

I certainly agree that phonemic symbols don’t matter that much. Most learners pay them no/little attention. However, people are visual animals and extremely sensitive to writing, whether the writing is conventional spelling or IPA symbols. My post is about conceptualizing FLEECE as a diphthong; this is not only phonologically well motivated but can also help some learners to ‘get’ it. I’m not precious about symbols, which is precisely why the post (including the graphic at the top) entertains various visualizations of the diphthong. But such visualizations can make a difference.

Obviously I don’t agree that “Either learners of English can imitate the sounds or they can’t”, or that hearing phonetic differences depends on whether one has “ears that work” or not. If I did, I’d give up my teaching and delete this website. In fact, I do have some success in helping people get better at imitating the sounds of English and making their ears work better. The most common feedback I get from clients is “now I hear so much more”.

Now I can see our comments after leaving my last comment.

How can anyone not agree with those things? I don’t understand. It’s obvious that some people can’t imitate some sounds no matter how hard they try, like the alveolar trill of many languages, for example. It’s also obvious that if your ears don’t work at all, i.e., if you’re deaf, you won’t be able to hear phonetic differences (or anything else for that matter). I think it follows that if your ears do work, but just not very well (e.g., you have hearing damage), then you won’t be able to hear phonetic differences as well as other people whose ears work better than yours.

The post is about whether people can be helped to perceive and produce FLEECE better by considering it – in accordance with phonological considerations – as a diphthong. My teaching experience tells me that they can.

Fair enough. I personally think it’s perfectly fine to transcribe the English vowel phoneme in see, peak as /i:/. Just because you transcribe the phoneme /i:/ doesn’t mean you’re saying it’s phonetically identical to the /i/ of French, etc. I don’t think I would make that assumption anyway if I were learning English. Plus there is a lot of phonetic variation in English. Some accents really do realize /i:/ as a monophthong (which is still phonetically different from the /i/ of French, etc.). If you’re learning English and you’re aiming for a specific accent, then hang out with speakers of that accent a lot. Preferably hang out with people with that accent who you like and want to be like. Just listen to them and imitate them, but don’t put too much conscious thought into it (which I’m sure little kids, who are arguably the best language learners, don’t do). I don’t think using the symbol /ɪj/ for the phoneme of me will help more than what I just suggested, especially if the person can’t pronounce [ɪ] correctly, like many learners of English. Instead of worrying too much about the phonemic symbols used for the vowels, listen to how native speakers actually pronounce them and imitate them. The phonemic symbols won’t magically give you the ability to pronounce a sound.

Could you please elaborate on this, Geoff:

“Phonologically – in terms of both phonotactics and liaison phenomena – FLEECE certainly belongs to the same class as FACE, PRICE and CHOICE. It does not form a natural class with PALM, GOOSE, NURSE and THOUGHT.”

Hello Andrej. In terms of ‘liaison’ or linking, FLEECE, FACE, PRICE and CHOICE link to a following vowel with j (unless hard/glottal attack is chosen), eg key‿event, day‿out, buy‿anything, enjoy‿it. (I would say the j is intrinsic to the vowel.) In terms of phonotactics, FLEECE goes with FACE, PRICE and CHOICE (plus GOOSE, GOAT and MOUTH) to make up the class of English vowels which may occur before another vowel within a morpheme, eg museum, chaos, giant, voyage (ruin, oasis, power). The so-called ‘long monophthongs’ of the old transcription system (FLEECE, PALM/START, GOOSE, NURSE, THOUGHT/NORTH) form no kind of natural class at all, except for having been the long monophthongs of an old accent spoken by the likes of your avatar. Whatever symbols you prefer, I think the vowels of SSB fall into the colour-coded categories on my chart.

Thanks!

Thank you – I’ve incorporated my answer into the main text, to clarify.

I disagree with the previous commenter, non-native speakers have a lot of trouble distinguishing the sounds which do not belong to their native language, so a phonemic transcription is a must. For example, speakers of Brazilian Portuguese often cannot tell the difference between the soft ‘th’, esp in initial position, and ‘d’, and they tend to mistake the hard ‘th’ by either a ‘t’ or ‘f’ sound. Also, they don’t seem to be able the hear the differences between ‘bad’ and ‘bed’ in the American accent, and they often pronounce both with /ɛ/, so the symbols are important to draw their attention to the fact that these sounds are not the same ones from their native language. After they learn how to produce them, and they’ll do so artificially, then they can hear them properly.

Now, I’ve been studying English for some time now, and even though I read somewhere the long high vowels of British accents were slight diphthongized, I didn’t try to apply that to my pronunciation consistently. Does this mean a long natural /iː/ is unacceptable? And is the starting point of the diphthong really /ɪ/? Because if /ɪ/ can be realized as /e/ this would make it the same closed diphthong of Conservative RP, as in ‘play’, which would really confuse foreign ears. If the starting point were /i/ that would make more sense. Does it apply to American accents as well? And the diphthong /ɛj/ in ‘face’ sound a bit like Cockney to me, is this the standard realisation for most accents in UK or just SSBE? Do the American accents still have /ej/? Sorry for my English, I’m not a native speaker.

Thanks for commenting! You raise many questions.

• If by ‘previous commenter’ you mean Nicholas, then I think you’ve misunderstood him. I don’t think he was denigrating phonemic transcription; I think he was stating an opinion that it doesn’t matter much whether phonemic symbols are phonetically accurate. (This opinion is often expressed as a justification for not updating Gimson’s half-century-old system.)

• You say a phonemic transcription is a must. It depends what you mean by a must. The percentage of the world’s English users who can make a phonemic transcription of it is negligible. It obviously isn’t a must for communication.

• You say or imply that production needs to be taught first. I think there is often too narrow a focus on articulation in teaching, and that production and perception need to be taught in parallel. You might have a look at this post.

• A monophthongal [iː] is ‘acceptable’ for FLEECE, but can sound affected (listen to the clips of Benedict Cumberbatch in this post) or foreign (German has a real [iː] which German speakers tend to use in their English). Like the other diphthongs, FLEECE often becomes monophthongal in running speech. More important, of course, is to keep FLEECE and KIT distinct.

• You say that ij makes more sense than ɪj. I’m sympathetic with this view; as I say in the post, “ij is defensible, highlighting the diphthong’s change in sonority rather than the change in quality”. The CUBE dictionary allows the user to show ij rather than ɪj.

• I think FLEECE is less diphthongal in AmE. Note that in AmE there tends to be a correlation between openness and length, so that seat is likely to be shorter than sat. On the other hand, there is a long tradition in America of representing FLEECE as ij or iy.

• Yes, ɛj is quite standard in SSB. Since diacritics are impractical, the question is whether cardinal 2 e or cardinal 3 ɛ is more accurate. The answer is the latter. In practical teaching terms, using ɛ is a good reminder to speakers of many languages that in its clearest form the SSB diphthong begins fairly open. To make a more general point: Most languages use three vowel heights, but English uses four. I find it helps many learners of English to open up their vowel space, to paint on a bigger canvas.

• Yes, AmE FACE is closer than SSB.

• Don’t apologize – good questions!

Thank you for your reply, Geoff, and for your answers. Well, about the phonemic transcription, I just think it’s very important for learners who are just beginning their studies, because they might not distinguish very well the sounds they hear, and English spelling is quite misleading, and that’s why, I think, most English dictionaries, even the ones for native speakers, have the transcription, which you don’t find often in dictionaries for other languages. And yes, maybe they don’t need to be completely accurate phonetically, but non-native learners might interpret them literally which leads to their ‘dated’ and ‘foreign’ pronunciations that you mention in your blog, and that’s why, I think, you devised your model.

About the /ɛj/ diphthong, the problem is that it sounds too open to me when I say it, so maybe, like you said, it happens because English distinguishes more vowel heights than other languages, because my /ɛ/ seems to be more open, and when I hear native speakers who supposedly have /ɛj/, it doesn’t sound as open to me. Surprisingly, I don’t think there is any significant difference between my /ɛ/, the one from my native language, and the one in ‘there’ or ‘pen’, but the FACE diphthong sounds less open to my ears. So maybe the /ɛ/ in FACE is less open than the one in ‘there’, between /e/ and /ɛ/, or it’s just my ears that are wrong.

Of course I agree that phonemic transcription has its uses. But I find it hard to reconcile claims that it’s very important for learners with the fact that few non-natives know or use it. It’s a bit like saying it’s very important to read music. Most can’t.

You’re right that the start of SSB FACE often isn’t as open as SQUARE or DRESS, but it’s nearer to cardinal 3 than 2. The nearest SSB vowel to cardinal 2 is KIT. As I’ve said elsewhere, “eɪ” is phonetically weird, since [e] and [ɪ] as demonstrated by the likes of John Wells are almost the same thing.

Yes, I agree that most learners can’t use it, as I have some colleagues who are English students and they don’t seem to make sense of the weird symbols in their dictionaries at all, even though at the beginning of every dictionary there’s an explanation of how to use them and examples of words which have each sound. However, it seems to me that those who do make use of the transcription improve their pronunciation at a faster pace, and there’s a reason why the transcription is there in the first place, in most learners’ dictionaries. Non-native learners who don’t reside in an English speaking country won’t have much chance to hear English everyday, so they might end up with more spelling pronunciations as a result. If I were to teach English to them, I would give at least an introductory lesson so they could learn the pronunciation of words by themselves in a dictionary, and it’s not that hard anyway. I think it’s particularly useful for English because of its spelling. Other languages probably don’t need it as much.

I agree /eɪ/ is strange, I was thinking about /ej/, to my ears it sounds quite different from /ɪj/, even if /e/ and /ɪ/ are close sounds. To me, /ɪj/ is more like /ij/, and I think this diphthong occurs naturally in my language when /i/ is followed by /z/ and sometimes /s/. So I think if the speaker can tell the difference between them, /ej/ could be an alternative, unless it sounds foreigner or affected. I don’t know if it does now.

In Dutch (as you undoubtedly know) there is a fundamental contrast between checked (“short”) i, like KIT and free (“long”) ee, like FLEECE. But it is not _quite_ the same; it cannot be, for if I use the Dutch contrast, I still get stick over my beaches sounding like b*tches. I think it’s something to do with the Dutch sounds being monophtongs, whereas natives start “bea-” with something like a schwa sound (but more rounded) and then j-linking it to the monophtong ee. By contrast, b*tch is almost “biyatch”.

I agree that ɪ = e, as in KIT, but I hear FLEECE as a more narrow diphthong, perhaps like [ɪ̝j]. I mean, it certainly doesn’t sound as open like the beginning of American FACE /ej/. So the same way FOOT is more open than the start of GOOSE, I think KIT might be more open than the start of FLEECE, unless ɪ ≠ e.

Thank you for pointing out a fact that should be more widespread on the Internet. As an example, whenever I watch Charlie but me on Youtube I hear “Charlay bit may”. However, not all Brits sound like that to me. Do you know what accent(s) has this jaw-dropping E sound?

Cockney and the broader Aussie accents and Brummie too, I suppose.

Thank you so much Dr.Wealthy, Again at first I thought he was joking about his penis enlargement herbs but I gave him a try,and he made herbal medicine and send it to me and told me within one week of using the product that my penis will be big,to my greatest surprise a week after using the product my penis was big and the happiness that was lost in my family was revived with the help of Dr.Wealthy. If you have a bad sex lifestyle, you can contact him if you have any health issues

wealthylovespell@gmail.com

Write him on Whats-app +2348105150446

Apologies for the tangential nature of this comment, but I’ve been eagerly awaiting your coverage of a question that’s long preoccupied me: the variation in the FACE vowel. To my non-native ears, a distinctive feature of Southern English is an unusually open realisation of this vowel – exemplified by Ricky Gervais’ pronunciation of the word “phase” in this clip: https://youtu.be/rc-sT0EpPdo?t=376 .

Yet I’ve found no scholarly confirmation of this observation. Might this be a dialectal feature (Estuary English, perhaps?), and if indeed it exists rather than being my auditory fancy, how might it relate to the traditional Cockney “/ɔɪ/-ish” pronunciation?

rc

PS. Hooray, I’ve managed to access those pages now – there must have been a minor glitch in early August, almost certainly at my end.