Popula culcha

English owes its position in the world to the power and influence of first the British Empire and later the USA; the establishment of America as Top Nation coincided with the emergence of modern popular culture. This differed from traditional folk cultures in that it was based on new mass media technologies and on capitalist democracy, through which collective taste could establish itself by quantity of sales. The USA developed the technologies, the markets and the new artforms; and American popular culture, much of it verbal in nature, conquered the world at lightning speed.

English owes its position in the world to the power and influence of first the British Empire and later the USA; the establishment of America as Top Nation coincided with the emergence of modern popular culture. This differed from traditional folk cultures in that it was based on new mass media technologies and on capitalist democracy, through which collective taste could establish itself by quantity of sales. The USA developed the technologies, the markets and the new artforms; and American popular culture, much of it verbal in nature, conquered the world at lightning speed.

Today we think of ‘American English’ as rhotic. That is, the most widespread and familiar kind of American accent preserves the historic r sounds which are indicated in spelling, but which back in London and much of England were lost except before a vowel – becoming ə or a lengthening of the preceding vowel. Paradoxically, however, popular culture as it spread from early 20th century America was to a large extent not rhotic. In particular, it came under three powerful phonetic influences: the South (notably African American English), the Northeast (notably New York City) and also to some degree the British Empire’s ‘Received Pronunciation’.

(It’s important to note that American r-loss was often less absolute than in England, many speakers using r variably, or exhibiting varying degrees of r-colouring, or an r-coloured NURSE vowel in otherwise non-rhotic speech. Therefore, less-than-fully rhotic American accents might be better described as hypo-rhotic than non-rhotic.)

Modern popular culture was substantially the creation of two ethnic minorities, both with histories of oppression. The emancipated slaves of the South created blues, ragtime and jazz, which they took to the cities of the North. In the West, the Hollywood studios were founded by Jews who had fled European poverty and persecution. The Warner brothers were from modern-day Poland, as was Goldwyn, while Mayer was born in Russia, Fox in Hungary, etc; they entered the USA through the Northeast, usually New York, where they picked up their English. Jewish New Yorkers were also particularly receptive to the new African American music, virtually industrializing it on New York’s Tin Pan Alley and Broadway. The creativity of these two peoples was unleashed in an economy that was erupting and had already surpassed that of Britain.

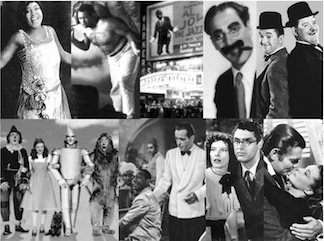

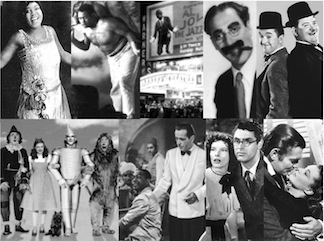

Interaction between the two minorities was central to early popular culture. 1927 saw both the first modern Broadway musical, Show Boat, and the first talking movie, The Jazz Singer. The former, composed by Jewish New Yorker Jerome Kern, is set in the deep South and deals with miscegenation; its most famous song is Ol’ Man River. The latter tells of a cantor’s son, played by Al Jolson, who paints his face black to perform songs like My Mammy. (Shortly after came America’s best known opera, the African American story Porgy and Bess, composed by Jewish New Yorker George Gershwin and famous for the song Summertime.)

Major recording stars of the 1920s included African Americans like Bessie Smith, Louis Armstrong and Paul Robeson, and Jewish Northeasterners like Jolson and Eddie Cantor. Hypo-rhoticity was a default. Here’s Smith, non-rhotic in millionaire, bootleg liquor and round their door:

And Robeson, non-rhotic in ol’ man river, tote that barge and the river Jordan:

Al Jolson, a real-life cantor’s son who was born in Lithuania and moved to Washington DC in childhood, was more variable, but here he’s solidly non-rhotic in I know where the sun shines best and the folks up North won’t see me no more:

Hollywood was not of course phonetically homogeneous, and not everyone there spoke with the accents of its founders. Just as jazz singing was taken up by rhotic Midwesterners and Westerners like Bing Crosby, so Hollywood developed stars of a more western and more rhotic kind – often with an outdoorsy or small-town image – like John Wayne and James Stewart; and the recently-deceased Shirley Temple was a local girl, discovered by an LA talent scout. But the studios tended to look northeastwards, towards New York and Europe, and heavily drew talent from both.

New Yorkers who moved to Hollywood included Humphrey Bogart, Eddie Cantor, Mae West, James Cagney, Barbara Stanwyck, Mickey Rooney, Alice Faye, Edward G. Robinson, Claudette Colbert and the Marx Brothers. Groucho Marx’s signature song Lydia the Tattooed Lady, written by New Yorkers Harold Arlen (another cantor’s son) and Yip Harburg, rhymes rhumba with number:

Groucho was non-rhotic enough to insert unwritten linking r into Lydia‿oh Lydia:

Warner Brothers’ most famous cartoon character Bugs Bunny was also a hypo-rhotic New Yorker, as was Popeye the Sailə Man – here arguing with his nemesis Bluto over whether Olive Oyl should be horizontal or pəjpendiculə:

Not all hypo-rhotic Northeasterners were New Yorkers. There were New Englanders, like Katharine Hepburn and Bette Davis. Here Hepburn says you’ve torn your coat, hello George and my farm in Westlake, Connecticut:

And here Davis says I never cared for you, you bored me stiff, no one ever called me darling, and we have the stars:

And not all Southerners were black. Oliver Hardy was from hypo-rhotic Georgia (his partner Stan Laurel of course was English). Here’s Hardy saying being a true Southerner, over there and pay the furniture‿off:

Hollywood’s large and hypo-rhotic British contingent included Laurel, Charlie Chaplin, Vivien Leigh, Cary Grant, Greer Garson, Ronald Colman, sisters Joan Fontaine and Olivia de Havilland, Basil Rathbone, Boris Karloff, Leslie Howard and many more; to these we might add Australian Errol Flynn.

The influence of RP on popular culture extended beyond the presence of actual Brits. There was also the influx of continental Europeans (Greta Garbo, Ingrid Bergman, Marlene Dietrich, etc) who tended to have acquired English on an RP-ish model. A third factor was the shadow cast over the American stage by the the old country’s literature and diction: an Americanized RP came to be known in some quarters as ‘American Theater Standard‘. Its influence certainly extended to the movies. The MGM musical Singin’ in the Rain (written by New Yorkers Betty Comden and Adolph Green) has a plot involving the arrival of talking pictures and the new need for stars to have good diction, ie to be pushed in the direction of RP:

So, despite the fact that the USA itself was substantially rhotic, much of Hollywood’s golden age output was distinctly low in rhoticity. Let’s look at a few iconic films.

According to the American Film Institute, the #1 male American screen legend was Humphrey Bogart (Cary Grant is #2; the top two ladies are Hepburn and Davis). Bogart’s most famous film, Casablanca, is a microcosm of Hollywood hypo-rhoticity.

Bogart himself is capable of being rhotic, especially in absolute phrase-final position. Here he says who was it you left me for and (from his Oscar acceptance speech) a little nicer here:

But if he had underlying r’s, they were often weakened or lost. Here are I heard a rumor those two German couriers were carrying letters of transit, I was misinformed, and what I’ve got to do you can’t be any part of:

And his who d’you bribe for your visa sounds to me rather like the kind of misplaced r-colouring I’d expect from an underlyingly non-rhotic speaker:

Bogart’s Casablanca sidekick Sam (Dooley Wilson) is a non-rhotic African American, lacking r in water under the bridge (not even linking r) and no matter what the future brings:

As Vichy Captain Louis Renault and Signor Ferrari there are two RP-speaking Brits, Claude Rains (until further notice) and Sidney Greenstreet (make a fortune through the black market):

The rest of the principals are continental Europeans who speak English on a non-rhotic model. Here are the day the Germans marched into Paris (Ingrid Bergman), what for (Paul Henreid) and I would advise you not to interfere (Conrad Veidt):

Another classic is the musical fantasy The Wizard of Oz (songs by the same Arlen & Harburg who wrote Lydia the Tattooed Lady). Narratively, this is the concussed daydream of a Kansas girl, Dorothy, who is appropriately played by rhotic Midwesterner Judy Garland. But the three magical companions she acquires are two hypo-rhotic Bostonians (Ray Bolger’s scarecrow and Jack Haley’s tin man) and a hypo-rhotic New Yorker (Bert Lahr’s lion). As they sing, they are sure ʃʊː to get a brain, a heart hɑːt and the nerve nəjv:

The good witch Glinda gives us an illustration of Hollywood RP or ‘American Theater Standard’. She is played by Billie Burke, an American who made her stage debut in London; Margaret Hamilton, on the other hand, is the wicked witch of the rhotic West. Here they are in aren’t you forgetting the ruby slippers:

Lastly, Gone with the Wind, the grandest film of Hollywood’s golden age and for decades its highest earner. This was a sweeping but politically incorrect saga of the old South, where as John Wells tells us “There was still a landed gentry, who retained a strong association with England and continued to send their sons to be educated there” (Accents of English p.469). A felt association between Southern ‘gentility’ and RP probably lay behind the casting of Brits in three of the four main roles (Vivian Leigh, Leslie Howard and Olivia de Havilland).

The fourth, Rhett Butler, was the most famous role of Clark Gable, the ‘King of Hollywood’. Gable was a rhotic Ohioan, and his Rhett was vague as to Southernness — but far from fully rhotic. Few syllable-final r’s survive in his I’ve always admired your spirit, my dear, never more than now when you’re cornered:

The servants of course are non-rhotic, including Hattie McDaniel who as Mammy was the first African American to win an Oscar; here she says Miss Scarlett and Savannah would be better for you:

So how have things changed? What is the status of these three hypo-rhotic influences on popular culture today? For two of them, I think the change has been remarkably slight. African American English continues to lie at the heart of popular music and its singing style. American Theater Standard may be a dated concept today, but the status of RP-type British English in popular culture is, I think, much as it ever was. I’ll say more about these two cases in the next two posts.

The biggest change by far has been the sidelining of hypo-rhotic Northeastern accents by the fully rhotic juggernaut of General American. As the 20th century progressed, America’s economic and demographic centre of gravity shifted westward. The heartland was largely white, gentile and rhotic, including many with Scots-Irish origins. They may have played a proportionally modest role in the creation of popular culture, but it was in the democratic nature of that culture to assimilate and reflect their speech.

The result was that hypo-rhoticity became increasingly marked, in both lower and higher status speech. By 1956 and Cecil B. DeMille’s remake of The Ten Commandments, even God was rhotic (thou shalt have no other gods before me):

So was Moses, played by Illinois-born Charlton Heston; whereas the backsliding, golden-calf-worshipping Dathan was played by hypo-rhotic Jewish New Yorker Edward G. Robinson, born in Bucharest.

One of the most forward-looking giants of popular culture was Walt Disney, unlike the original Hollywood moguls a midwestern gentile. The rhotic Disney provided the voice for his own creation Mickey Mouse:

Though his vision was rooted in small-town America, Disney was a technical and commercial pioneer, an early user of sound and colour who expanded into new areas like theme parks and television. The new medium of TV certainly reinforced General American speech. Where Hollywood had been a dream factory, relatively cosmopolitan and international, TV was more national and more reflective of real people’s lives, from news coverage to game shows with ‘ordinary’ contestants. In the early days of the late 1940s and 1950s, America’s ‘Mr Television’ was hypo-rhotic New Yorker Milton Berle, here telling Elvis Presley to stick to Heartbreak Hotel and stay away from the Waldorf:

But soon America’s TV icons were more typically rhotic Midwesterners like talk show host Johnny Carson and newsman Walter Cronkite, ‘the most trusted man on TV’, who announced to Americans the assassinations of Kennedy and King, and the Apollo moon landing:

The American moon mission may have been initiated by the hypo-rhotic President Kennedy, but it would surely have been unthinkable for the first one there to speak anything but GenAm. Humphrey Bogart may have stuck his neck out fə nobody, but Ohioan Neil Armstrong made one giant leap fɹ mankind:

In the early 1970s Johnny Carson moved his Tonight Show west from New York to California. A lot of publicity has been given to the show’s recent return to Manhattan after forty years. But where the last host, Jay Leno, was a variably rhotic New Englander, new man Jimmy Fallon is an upstate New Yorker who speaks GenAm. Geographically, The Tonight Show has gone back east; phonetically, it’s gone back west.

Today’s most famous American TV stars are surely the Simpsons. Declared by Time Magazine in 1999 to be the 20th century’s greatest TV show, and still going strong, the Simpsons are the modern equivalent of the 1960s cartoon family the Flintstones. But Fred Flintstone and his pal Barney Rubble were prehistoric hypo-rhotic Brooklynites. Homer Simpson’s Springfield is in so many ways – including rhoticity – a symbol of General America:

Great post!

In the “Singing In the Rain” excerpt, it is amusing to note that the elocution teacher hypercorrects, using a RP-ish BATH-type vowel not only in “can’t” but also in “stand”.