The King’s Speech: Charles III’s RP accent

My latest video analyses King Charles’s RP accent. Received Pronunciation (RP) was the upper class accent during the last century or so of the British empire. There aren’t that many speakers of classic RP left. Huge social changes in Britain starting in the 1960s rapidly made it sound very posh and old fashioned. Today’s standard accent in the South of Britain is Standard Southern British (as defined in the Handbook of the IPA, p. 4).

Charles was just old enough for his accent to be fixed before the Swinging Sixties. (On the other hand, both his sons speak SSB.)

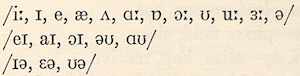

vowel symbols for RP by Gimson 1962

Another thing that unfortunately got fixed before the Swinging Sixties was the set of vowel symbols for British English that you find in most dictionaries. (A. C. Gimson proposed the symbols in his Introduction to the Pronunciation of English, 1962). This means that King Charles is one of the few people who actually sounds like these symbols.

King Charles’s RP: Vowels

For example, the vowel of the word PRICE in modern SSB begins quite back in the mouth, ɑj:

But King Charles’s RP accent actually pronounces it like the familiar symbol aɪ, beginning with a more front quality, as in ‘I’ and ‘recent times’:

He also pronounces the vowels of DRESS and FACE like the familiar symbols e and eɪ, as in ‘ahead’ and ‘plays’:

In SSB those are more open, ɛ and. ɛj:

On the other hand, in today’s SSB the vowel of CHOICE is quite close, oj:

But the King has the more open RP vowel, ɔɪ. This means that when he says ‘joy’, it begins rather like the word ‘job’:

He even has a couple of vowels that are actually posher and more old fashioned than the symbols! One is the vowel of GOAT. The familiar symbol əʊ begins with schwa, as this vowel still does in SSB:

But King Charles’s RP accent begins the vowel further forward in the mouth, ɘʊ:

And his MOUTH vowel is quite different from today’s aw. It starts a bit further back in the mouth and with no lip rounding at all, ɐɤ, as in ‘extremely proud’:

(Brits sometimes make fun of this posh old vowel by writing ‘house’ as ‘hice’.)

A difference in his weak syllables is the so-called happY vowel. Today, SSB speakers have the same vowel in both syllables of ‘deeply’. But in King Charles’s RP accent, the word ends with the lax /ɪ/ of KIT:

King Charles’s RP: Consonants

Let’s move on to consonants. One posh old-fashioned feature here is the weakening of the t sound to a kind of s. This might be the word ‘sing’:

But it’s actually the second half of ‘fighting’:

If you’ve seen my video on aspiration, you’ll know that in SSB t is typically affricated. This means that speakers pronounce it with a little s-type release, tˢ. When t is in a weak position, the King Charles’s RP accent often weakens it all the way to a fricative. This is called spirantization. You can also hear spirantization in Liverpool and Ireland. Here the King spirantizes t in ‘devoted’ and ‘planet’:

Sometimes the King uses American-style t-voicing, as here in the ‘nineteen forty-seven’:

But one kind of t-weakening that posh people like the King never do is pronouncing it as a glottal stop ʔ before a vowel. The new Prime Minister Liz Truss uses such a glottal stop here in ‘Britain is the great country i[ʔ]is today’:

King Charles’s RP: General

Weakening is something that the King does more generally. Commentators have occasionally described him as ‘mumbling’. But in my book English After RP I actually devote a chapter to this relaxed, weakened style of speech. I think it was characteristic of many RP speakers. Here are some sounds that King’s Charles’s RP accent reduces or eliminates altogether. First, ‘trying circumstances’:

‘biodiversity’:

‘ladies and gentlemen’:

‘the whole commonwealth‘:

We all do this kind of thing when we’re chatting casually. But those clips are examples of formal public speaking. Sometimes the King races through his words at lightning speed:

It’s not easy to say ‘incredibly difficult’ at that speed! I think this shows that what we’re not talking about here isn’t laziness but an actual style of speaking. The King does often emphasize words or syllables. But, as I show in the video, he frequently does this not by articulating clearly, but by moving his whole head or body.

I certainly don’t claim that this analysis of the King’s speech is in any sense complete. For example, I haven’t even mentioned voice quality. But I hope I’ve managed to illustrate a few differences between old RP and modern SSB.

In listening to the King’s pronunciation of ‘I’, I hear some mid-centralization of the 1st element of the diphthong and a very exaggerated 2nd element. I hear something like [ɜiːj(ə)]. Excluding the [jə] part at the end, it sort of reminds me of a “Canadian raised” diphthong on this side of the pond.

The King’s diphthong in ‘(recent) times’ sounds more like what I think of as [aɪ].

However, in any case, your overall point that the King’s vowels are different from “SSB” vowels still stands.

Listening to the king I suddenly thought I was listening to my late father and his brother. They would have been only a few years older than his majesty