Generality

I’m very flattered that this blog has been cited by two important books this year, Alex Rotatori’s L’inglese medico-scientifico and Alan Cruttenden’s latest revision of Gimson’s Pronunciation of English (8th edition), which adopt one or two transcriptional practices I’ve been using for years (both use ɛː for SQUARE; Alan also switches to a for TRAP). I can heartily recommend both books. My lack of Italian prevents me from assessing Alex’s properly, but it’s hard to imagine a better guide to current BrE pronunciation for Italians than Alex; I imagine its usefulness extends way beyond the medical world. Alan’s book will naturally have a wider readership and is, simply, an essential reference work on the pronunciation of English(es) today.

I’m very flattered that this blog has been cited by two important books this year, Alex Rotatori’s L’inglese medico-scientifico and Alan Cruttenden’s latest revision of Gimson’s Pronunciation of English (8th edition), which adopt one or two transcriptional practices I’ve been using for years (both use ɛː for SQUARE; Alan also switches to a for TRAP). I can heartily recommend both books. My lack of Italian prevents me from assessing Alex’s properly, but it’s hard to imagine a better guide to current BrE pronunciation for Italians than Alex; I imagine its usefulness extends way beyond the medical world. Alan’s book will naturally have a wider readership and is, simply, an essential reference work on the pronunciation of English(es) today.

Like me, both authors avoid “Received Pronunciation (RP)” as the name for a default reference accent of contemporary British English. They adopt “General British (GB)”, a term coined by Jack Windsor Lewis in 1972, and it’s nice to see recognition of Jack’s influence. Jack coined the term as part of a parallel treatment of British and American pronunciation, “General British” matching the well-established term General American. It was thanks to Jack that the 1974 Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary published “for the first time in any major EFL dictionary, its (100,000) entries in American pronunciation as well as British” – so let’s also take the opportunity to salute the 40th anniversary of that landmark.

Like me, both authors avoid “Received Pronunciation (RP)” as the name for a default reference accent of contemporary British English. They adopt “General British (GB)”, a term coined by Jack Windsor Lewis in 1972, and it’s nice to see recognition of Jack’s influence. Jack coined the term as part of a parallel treatment of British and American pronunciation, “General British” matching the well-established term General American. It was thanks to Jack that the 1974 Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary published “for the first time in any major EFL dictionary, its (100,000) entries in American pronunciation as well as British” – so let’s also take the opportunity to salute the 40th anniversary of that landmark.

Both Jack and Alan intend merely a name change. Jack has long disliked the label RP and he proposed “General British” as a straightforward replacement. Alan on the other hand would happily stick with RP but has felt obliged to drop it. For me, this is not about losing a name; it’s about gaining a distinction. RP is the established name of the classic 20th century accent codified by Jones, Gimson and Wells; we can’t and shouldn’t rewrite all the books that describe it as such. But social and phonetic change has brought us to a point where it’s potentially confusing to extend that same term to contemporary speech. So I prefer to keep the term RP for the earlier accent, and to think of modern speech as something else.

Among academics, SSB (Standard Southern British) is the most established term for RP’s “modern equivalent”, as it was described at the end of the last century by the Handbook of the International Phonetic Association. (“Standard” is another word Jack doesn’t like, but it’s used very widely for linguistic systems that have prestige and are used as norms for teaching.) I don’t know how general the new adoption of “General British” will be. I like Jack’s and Alan’s “General” approach, acknowledging a useful range of accents and pointing out that many of the differences between them are of little importance. But, for anyone who’s thinking of adopting the term “General British”, I think it’s important to keep in mind how different the status of General American is from that of any British accent.

1. General American is a majority accent

GenAm is remarkably general, in the general sense of the word general. This denotes characteristics pertaining to all or most of a group or thing, all or most of the time; a further connotation has to do with holistic features as opposed to specific details. (A general strike involves most or all workers; a book for the general reader can be read by the majority who lack specific knowledge; a general impression of something captures it as a whole but not in detail.) According to Jack, “General American is spoken by about two-thirds of the US population”. John Wells in Accents of English: “‘General American’ is a term that has been applied to the two-thirds of the American population who do not have a recognizably local accent” (118).

There is no majority accent in Britain. When I travel to teach, speakers of languages as different as Italian and Japanese tell me rather apologetically that they find BrE harder to understand than AmE; I don’t hear the converse. If this is a general phenomenon, it may be partly attributable to the greater generality of GenAm compared with the greater accent diversity in BrE.

2. Broadcasting

Opinions differ on whether GenAm is becoming more general or less general. On the one hand, it’s encroaching on the traditional accents of the deep south (except in pop music); on the other hand, the eminent sociolinguist William Labov draws attention to various processes of diversification. But certainly – this is my second point – GenAm has a high degree of generality in broadcasting, where it’s even more general than it is in the population as a whole. It’s by a wide margin the most-heard accent from news to soap operas, from sitcoms to advertizing. Here’s a range of contemporary supermarket ads:

RP once had a similar degree of generality in broadcasting. Back in the 1970s when Jack started calling RP “General British”, supermarket adverts sounded like this (Tesco, Co-op, Sainsbury’s, Morrisons):

Such voices were generally male and generally RP. But since the 1970s, broadcasting in the UK has been undergoing a process of marked diversification. As I discussed in a previous post, American broadcasting democratized by adopting the majority accent. British broadcasting has democratized in a radically different way, precisely because there is no majority accent – namely by opening its doors to diversity. Here’s a contemporary campaign from the supermarket Morrisons:

Even the snootier supermarket Waitrose is represented by a Liverpudlian with STRUT=FOOT and weakening of final k and t:

Diversification has not been restricted to supermarket ads, which of course try to appeal to as wide an audience as possible. In many areas, where there was generally RP, now there is diversity. Back in the 1970s, BBC TV brought the nation together in the early evening magazine show Nationwide. The perspective was “nationwide” 70s-style, ie hosted by RP speakers like Sue Lawley:

and Bob Wellings, here interviewing the band Led Zeppelin and comparing them with the Beatles:

For the 21st century the BBC devised a modern version of Nationwide and called it The One Show. A modern “nationwide” approach required accent diversity. When Led Zeppelin’s Robert Plant returned 40 years later he was interviewed by Christine Bleakley (Northern Ireland) and Adrian Chiles (Birmingham):

In the 1970s, astronomy was brought to TV audiences by the late RP-speaking Patrick Moore:

Nowadays we have the wonders of the cosmos described by Professor Brian Cox (from Oldham, Greater Manchester):

Back in the 1970s, BBC business presenters didn’t have Tyne-Tees accents like Steph McGovern’s:

and if stockbrokers were invited on TV for interview, they didn’t have the London-Estuary accent of Hargreaves Lansdown’s head of equities Richard Hunter:

Note that even the most traditionally stigmatized accent types are no longer excluded. We heard above Liverpudlian Roger McGough advertizing Waitrose; he’s also been the voice of classical music radio station Classic FM. TV documentaries, too, can be narrated in a Liverpool accent with SQUARE=NURSE (early stage carbon dioxide poisoning… it sucked air through the filter):

Among newsreaders the majority accent is still the SSB type, but diversity has already risen to previously unthinkable levels. Britain’s foremost newsreader, of course, is the BBC’s Welsh-accented Huw Edwards:

Here again is Birmingham-accented Adrian Chiles, reading the news on BBC radio:

The commercial channels have diversified too. Here’s an ITV news bulletin with a rhotic introduction and a newsreader with BATH=TRAP:

I see no reason to assume that this process won’t continue. In 1962, A. C. Gimson wrote of “the influence of radio in constantly bringing [RP] to the ears of the whole nation” and of a consequent tendency of accents “to be modified in the direction of RP, which is equated with the ‘correct’ pronunciation of English.” By the same token, as diversity increases in the media, so the next generation will feel even less pressure to modify, which portends an increasing proportion of non-SSB accents heard in increasingly broad forms in a widening range of situations.

Prof Brian Cox illustrates the fact that accent diversification has taken place not only in broadcasting but also in higher education. Here is Mancunian Jon Butterworth, UCL Professor of Physics and one of the discoverers of the Higgs boson at CERN:

As Jack Windsor Lewis puts it,

today a very large majority of the most highly educated inhabitants of Great Britain have markedly regionally-affiliated speech.

3. Regionality

GenAm is far more regionally general than SSB-type speech: as a majority accent, it is spoken by large numbers over vast areas of the USA, from Alaska to Nebraska, in Vermont and Florida, in California and Hawaii, and so on. By contrast, the number of SSB speakers is markedly higher in a single region, the southeast of England, and markedly lower outside this region.

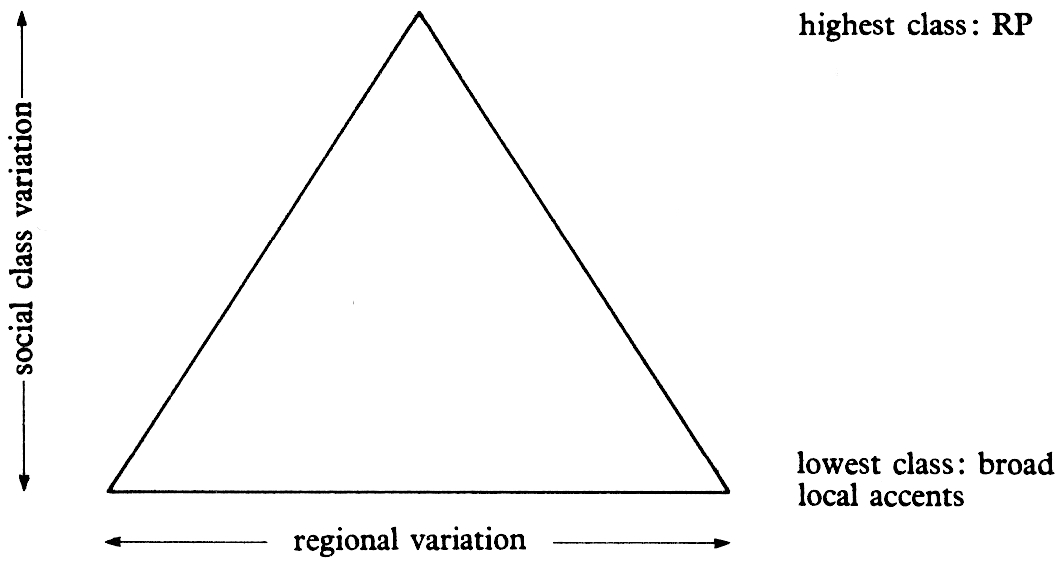

RP used to be described as “non-regional”. John Wells’s Accents of English illustrated this with the classic pyramid diagram:

“The pyramid is broad at the base, since working-class accents exhibit a great deal of regional variation. It rises to a narrow point at the apex, since upper-class accents exhibit no regional variation in England” (14).

“The pyramid is broad at the base, since working-class accents exhibit a great deal of regional variation. It rises to a narrow point at the apex, since upper-class accents exhibit no regional variation in England” (14).

But RP was regionally affiliated. It was not some democratic generalization across a range of regional pronunciations: it was the cloning of the pronunciation of the southeastern English upper classes. The southeast determined not only what RP was, but also what it would become: SSB resulted from RP’s shifting in various ways towards the lower-class accents of its region. An example of this was the switching of the initial elements of the PRICE and MOUTH diphthongs, from a and ɑ to ɑ and a respectively. (SSB also has certain features that didn’t come from popular southeastern speech; I’ve illustrated the vowel system at length here.)

SSB remains a higher-class minority accent, but it extends further down the social scale than RP did. Crucially, SSB excludes the thin upper crust at the top, whereas this upper crust was an inalienable sub-type of RP which those who clung to the RP “brand” could not disown. So SSB is relatively less high-class and less socially narrow than RP was, sufficiently so to free it from the stigma which, as I explained in a previous post, became attached to the upper class.

As the wording on my website has run for years, “the accent of the higher socio-economic groups in England (particularly those of London and the southeast) continues to enjoy a degree of prestige.” This is why I use it myself as a default teaching standard for BrE. Tourists will hear it in various public address systems. It’s still the most-heard accent in areas of the media like newsreading and movies aimed at an international market. Of course much of this stems not from any geographical scattering of its speakers but from the fact that the higher socio-economic groups of the southeast themselves continue to have disproportionate clout.

Additionally, and profoundly, RP still acts as a kind of phonetic “dark matter”: not much in evidence itself, but exerting a gravitational pull over a vast area. From Ireland to Australia, from Scotland to South Africa, many speakers modify their accent towards it, especially in more formal contexts like newsreading. Throughout large parts of the ex-empire, the very concept of a broad or mild accent often implies relative distance from RP.

There are certainly speakers who grew up outside the southeast of England but who speak SSB, or something like it. As an internationally-known example, take controversial personality Jeremy Clarkson, a Yorkshireman with an SSB accent:

Clarkson is a “public school boy”, educated at the posh private school Repton, founded 1557. Back in the 1970s, when Clarkson attended Repton, there was a general public school accent: it sat at the top of John Wells’s pyramid and Jack Windsor Lewis called it “General British”. This isn’t so now. There’s ever-decreasing pressure for even the privileged to clone the speech of the southeastern elite. We’ve already heard Professor Brian Cox, who was privately educated at a school belonging to the HMC, one definition of a “public school”. Or take footballer Will Hughes, who attended the same school as Jeremy Clarkson, Repton; but whereas Clarkson attended Repton in the 70s, Hughes (born 1995) attended in the 21st century, and it left his Derby accent intact, including BATH=TRAP and STRUT=FOOT:

I’ve met a range of young public school products with northern and London-Estuary accents. One was a student starting university who was born in London, where his affluent parents have always lived, but who had just left a posh northern-England boarding school; his accent, like Will Hughes’s, had BATH=TRAP and STRUT=FOOT. Apparently in the 21st century it’s possible for a public school education to erase a higher-class southern accent rather than inculcate one.

Importantly, RP’s homeland was England, and this is still more true of SSB. In the international context, SSB-type pronunciation is known simply as “British”, contrasting with American, Irish, Australian, etc. But closer to home, labelling often needs to be more specific. Unfortunately the repetitive form “English English” is too awkward for general use. At least “Standard Southern British” makes no claim to represent Scotland. (The location of the implicit north-south divide is vague – perhaps usefully so.) When I started my website, my illustrated descriptions of current BrE were aimed chiefly at international non-natives, and I often referred simply to “Standard British” – the British accent most used as a teaching standard. As my readership grew it became clear that this wouldn’t do, and subsequently I’ve reintroduced the “Southern” in many places, along with some references to “EngE” (which doesn’t look as bad as the full form).

It’s something of a stretch to refer to SSB-type speech as “General British”, affiliated as it is to England, and lacking even the mandate of a British majority. Next year the International Congress of Phonetic Sciences will be held in Scotland’s biggest city, Glasgow, which last month voted in favour of Scottish independence and the break-up of Great Britain altogether. If you’re intending to give a talk at ICPhS 2015 on SSB-type speech, I’d think twice before standing up there and referring to it as “General British”.

So GenAm is more regionally general than SSB. Furthermore – this is my fourth point – GenAm is more socially general. Across vast tracts of the USA, GenAm can readily be encountered from teachers, bartenders and checkout clerks. By contrast, even within its own region, SSB is associated with higher socio-economic groups.

For the kind of classic RP accent associated with poshness and even villainy, Alan and Jack use the decidedly odd term “Conspicuous General British”. I’m not sure what it would mean to be conspicuous and general. Conspicuously widespread?? No: the quality which that accent has to a conspicuous degree is not generality but high social class. By contrast, GenAm is socially general, so there couldn’t be anything as bizarre as “Conspicuous General American”. GenAm emerged because of socio-cultural democracy: a mass accent with humble Scots-Irish roots, it inexorably marginalized the accents of both the northeastern elite and the southern gentry. There is no Conspicuous General American because General American, unlike any British accent, is general.

5. Phonetic generality

Lastly, GenAm is phonetically more general than RP-type descriptions have been. Recall that the word general often refers to overall essentials with an allowance for differences in detail. This certainly characterizes GenAm. John Wells: “Obviously, GenAm is not a single unified accent” (Accents, 470). You can’t identify any one speaker who exactly embodies it; this is why, as John points out, “dialectologically… it is of questionable status” (10), and why William Labov declares that “there isn’t any such thing as General American”. GenAm is a convenient model which insists on essentials, like the FLEECE-KIT distinction, while allowing other points of variability, such as commA~STRUT and PALM~THOUGHT. GenAm is a broad church.

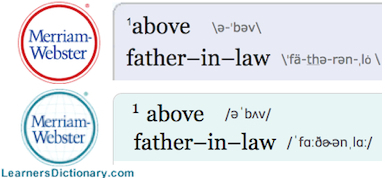

This can be seen in the online transcriptions of Merriam-Webster, the bestselling American dictionary publisher. The main Merriam-Webster site has commA=STRUT but PALM≠THOUGHT, while the Merriam-Webster Learners Dictionary conversely has commA≠STRUT but PALM=THOUGHT:

By allowing GenAm to include such points of difference, the generality of the accent expands by many millions of speakers. In the US, PALM=THOUGHT may have a more western flavour, PALM≠THOUGHT more eastern. Such details are important for a dialectologist, but not for the general public or the learner.

By allowing GenAm to include such points of difference, the generality of the accent expands by many millions of speakers. In the US, PALM=THOUGHT may have a more western flavour, PALM≠THOUGHT more eastern. Such details are important for a dialectologist, but not for the general public or the learner.

By contrast, RP’s social specificity led to phonetic specificity. There developed a keen sensitivity to what counted as RP and what (or who) did not, because your status depended on it. John Wells, discussing on his blog the shift from the old-fashioned happY=KIT to modern happy=FLEECE, referred to the latter as a “newly respectable pronunciation” (my emphasis). Possibly the wording was ironic – John of course is unprejudiced and more knowledgeable about accent diversity than anyone – but it certainly referenced the classic view that non-RP was non-respectable. In another post, John told readers

There are many English and Welsh people who pronounce the STRUT vowel pretty much the same as schwa. So do many, perhaps most, Americans. For them, we could reasonably write both vowels as [ə]. So it would be reasonable for EFL learners not to worry too much about the contrast. Millions of native speakers… say [əˈbəv] and [əˈnəðə(r)]. You can too, if that’s easier.

All very true. Then came the kicker, the one-line final paragraph:

But not if you want to speak RP.

For any EFL reader believing that only RP is correct or respectable, the meaning would be clear.

John’s Longman Pronunciation Dictionary includes various alternative pronunciations, but the RP/non-RP frontier is clearly signposted. The section sign § marks out “Pronunciations widespread in England among educated speakers, but which are nevertheless judged to fall outside RP” (xix). Examples include the LOT vowel in one and BATH=TRAP. Such pronunciations are widespread, they’re educated, and today they can be heard from public schoolboys and BBC newsreaders; but instead of being included within standard variation, à la GenAm, in LPD they are “judged to fall outside”.

The RP ethos pretty much guaranteed its own demise. Since the period around 1962, universities were filled more and more with students who felt no pressure to adopt RP, including linguists and phoneticians who would go on to become authorities on English and its pronunciation. The RP ethos alienated many of them, giving them the impression that they “fell outside” –even if they were close to the frontier. I’ve often heard, with varying degrees of defensiveness, the kind of sentiment expressed in this lecture by Professor Jennifer Jenkins: as soon as she reaches the topic of RP (5:04) she feels obliged to say that she couldn’t call herself a speaker of it. This would surely have mystified any non-natives in her audience who thought (quite rightly) that she sounds very much like a BBC newsreader.

Jennifer Jenkins Talking it through whose accent

Jennifer Jenkins addresses issues of pronunciation

So much for RP. How broad a church is our teaching model for contemporary BrE pronunciation? We could stick to the old “Received” approach, conservative, narrow, anathematizing. Or we could define it relatively loosely, like General American, so as to encompass more diversity. For instance, Britain has changed from being a place where using the same vowel in BATH and TRAP excluded you from newsreading to one where it doesn’t. BATH≠TRAP may have a more southern flavour, BATH=TRAP has a flavour of the north and of popular music. If we allow our teaching model of BrE to include both BATH=TRAP and BATH≠TRAP, then the model’s generality expands by millions of speakers.

What I value so much in Alan Cruttenden’s Pronunciation and in the diamond mine of Jack Windsor Lewis’s blog is their “General” approach to teaching – ecumenical, incorporating diverse accents and acknowledging that many of the differences are of little consequence. It’s a shift from a fall-outside to a fall-within approach, and it’s less likely to engender among native speakers the conviction that “I couldn’t call myself a speaker”. This kind of approach encourages teachers to prioritize: we need to emphasize core contrasts like FLEECE≠KIT and TRAP≠STRUT, while details like BATH~TRAP and STRUT~commA are less important variables (unless, as in the case of actors, a specific accent has to be taught).

There are situations where it’s less appropriate to bombard non-natives with diversity, eg lower-level teaching and some kinds of dictionary. And it’s fine to learn a single specific accent for speaking purposes. But any non-native wanting or needing to understand broadcast or academic British speech – overseas students at British universities, for instance – must expect to deal with diversity.

However, it’s unrealistic to accommodate much of the diversity illustrated above under the umbrella of a single “accent”. John Wells has sometimes referred to “son of RP“; it might be more realistic (and less sexist) to talk of “RP’s children”. So a general approach to teaching BrE is surely right, precisely because Britain doesn’t have a general accent along the lines of GenAm. In fact, with the ongoing diversification of accents in areas like broadcasting and the centrifugal pull of devolution, this strikes me as a very odd time to start using the 1970s coinage “General British”.

The term may yet catch on, although its abbreviation “GB” is pretty useless as a search term, since it already stands for “gigabyte” and “Great Britain”. Publishers may well be attracted to “General British”, as it implies The Only Accent You’ll Ever Need – which, as far as listening is concerned, it certainly isn’t. But I’m not inclined to use the term myself, unless perhaps its adoption becomes… general.

As you can imagine, I found your latest blog (on RP and the like) very interesting. I have always disliked the name RP. The name GB has never appealed to me, despite JWL’s enthusiastic campaigning for it. As you have explained, this accent is neither General nor British. I could live with SSB, but it’s not very memorable, nor particularly accurate.

In most of what I have written on English pronunciation I have used “BBC Accent” or “BBC Pronunciation” as a name for the standard accent. Peter Trudgill and Peter Ladefoged also adopted the term. My initial reason for using it was to help all the students (particularly foreign ones) who were doing projects that seemed to require recording a number of RP speakers. As you know (ref your story of Jenny Jenkins) it is extremely hard to get anyone to admit to being an RP speaker. To do so is clearly found embarrassing. So I advised them to record speakers from the BBC, and I was very specific about which speakers they were to choose. These were English-born professional speakers employed by the BBC as newsreaders and announcers on BBC1 and BBC2, Radio3 and Radio4. The same accent may of course also be heard on other broadcast channels. In this way, students were able to access unlimited quantities of high-quality recorded speech, free of charge and free of embarrassment, for their research. And, as I have pointed out, there is much less of a suggestion of being at the top of the social-class pyramid with BBC speakers.

The argument against the BBC name is always the same: that the old rigid uniformity of broadcast English has now given way to a much wider range of accents. This is obviously a matter of opinion; it may well be true of broadcast speech in general. However, if you restrict the definition to the group I specified, which automatically excludes Huw Edwards and, a more spectacular example, Neil Nunes, what I find really striking is just how little variation there is, even today. Phoneticians tend to concentrate on small deviations from an imagined norm, but for most purposes I believe there is a remarkably homogeneous body of speakers working for the BBC that provides a valuable model.

Dear Professor Roach,

Could you reveal who those speaker you told your students to record are?

Thanks for all the examples of accents. For your collection, don’t forget Professor Peter Higgs himself, Nobel laureate from Bristol.

The emergence of regional accents in the professions has progressed throught the entire 20th century, and perhaps earlier, possibly starting with science and engineering. Did John Smeaton, 1724-1792, adopt the RP of his day, or did he keep his northern accent? Today, the BBC and the inns of law have finally given way. Also the armed forces: fifty years ago my CO could accuse me of not speaking English, today we hear generals with my same regional home counties accent. That doesn’t mean RP has disappeared, it means that attitudes have changed.

RP has always been subject to change. Jones gave a narrow window onto the RP of the late 19th century. Gimson updated the record in the 1960s. More changes in RP pronunciation have been recorded since. Alexander Ellis (1814-1890) would have heard rhotic RP still spoken, but acquired nonrhotic RP himself. When Smeaton was a child, new generations of RP speakers were probably biting their teeth on the new TRAP-BATH split (and lived to hear the first use of the term “Received Pronunciation”). It seems strange that change in RP pronunciation should be cited as a reason for changing its name after more than 200 years of constant change. It’s certainly a cumbersome name, that needs constant explanation. But that’s because that meaning of “received” has long been an anachronism, reason enough for revising it. But I woud advocate keeping it, for the sake of continuity. RP is one sociolect among several of SBE, isn’t that good enough?

I’m not even English and even I can tell Richard Hammond is from the West Midlands. Listen to the way he says “now” and “cars” in his clip above. James May’s accent is admittedly harder to place, but his MOUTH vowel is very West Country. His STRUT vowel has a more mid-centralized quality than what you get in the London area. Hammond’s does too I think.

Readers of this blog post may be interested in this riposte: http://www.yek.me.uk/Blog.html#blog490

Thanks to Petr for providing the link to JWL’s blog. Jack’s piece interprets my article as a set of arguments against his term “General British”. Rather, the article is a description of various ways in which GenAm differs from the past and present standard/reference/teaching accents of Britain. I thought it was particularly worth writing, since a couple of books this year have adopted “General British” without making it clear to their readers how different the position of this accent is from that of General American, which the term “General British” explicitly parallels. If people decide to adopt “General British”, I think they should at least be aware of the differences. Moreover, it seems to me that in some important areas this kind of accent has markedly decreased in generality over the last generation or two, as accent diversity has increased. This is precisely why I value so much the coverage of diversity in JWL’s blog and Alan Cruttenden’s Pronunciation – which I did my best to highlight in the article. The article is not an attack on Jack’s ideas as he suggests, and in fact I repeatedly go out of my way to praise Jack’s work.

I do think it’s important to move on from RP, but I’m not obsessed with names: if the term “General British” is adopted generally, I may make use of it myself. The strongest of the arguments against it, it seems to me, are 1. it implies some kind of general status throughout Britain (there were justifiable complaints on these grounds against my earlier use of “Standard British”); 2. the abbreviation “GB” is problematic as it’s established for “Great Britain”. Francis Nolan’s term SSB seems to me rather better (or John Wells’s “Southern British Standard”, which has not been so widely adopted). I’ve heard it said that SSB is cumbersome, but nobody objects to BBC and CIA on the grounds that “British Broadcasting Corporation” and “Central Intelligence Agency” are a mouthful. If you do online searches for “SSB” or “SSBE” you get quite a lot of relevant academic research, but “GB” is useless, so you end up having to use the full form “General British”, and that is cumbersome.

Jack criticizes my “logic”; needless to say I disagree. Readers can follow Petr’s link and make up their own minds. However my recollection that the IPA Handbook was published in 1990 rather than 1999 was a straightforward blunder, and I’m grateful to Jack for prompting me to amend the article accordingly.

There are many examples of younger speakers who speak in RP.

For example, Wilfred Frost, the son of David Frost and his wife, Lady Carina Fitzalan-Howard, daughter of the 17th Duke of Norfolk. Wilfred was educated at Eton and Oxford and you can see him every weekday morning on CNBC:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Py9DBkRLZ7I

Or Mark-Francis Vandelli Orlov-Romanovsky, the star of Made in Chelsea, the son of an Italian industrialist and Russian princess:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oZfDrha09lg

Does anyone know where I can find a blank “General Form” to fill out?

Nice read

Thank y9ou for sharing