Accent of the Year / sibilants in MLE

The most dramatic events of 2011 in Britain took place while I was teaching on UCL’s Summer Course in English Phonetics. Of course I’m referring not to my classes but to the summer riots. Reaction to these meant that the speech of young inner-city Londoners got far more media exposure this year than before. An uninformed rant about “Jamaican patois” by a celeb-historian became notorious, but was fortunately corrected by the expert Paul Kerswill, in this brilliant and concise talk on Multicultural London English. MLE’s new visibility makes it a natural candidate for Accent of the Year.

The most dramatic events of 2011 in Britain took place while I was teaching on UCL’s Summer Course in English Phonetics. Of course I’m referring not to my classes but to the summer riots. Reaction to these meant that the speech of young inner-city Londoners got far more media exposure this year than before. An uninformed rant about “Jamaican patois” by a celeb-historian became notorious, but was fortunately corrected by the expert Paul Kerswill, in this brilliant and concise talk on Multicultural London English. MLE’s new visibility makes it a natural candidate for Accent of the Year.

Aside from its reversal of London h-dropping, MLE has been described mainly in terms of its vowels. I haven’t seen much discussion of its hissing sibilants [s] and [z], though I find these among its most striking features.

For many (me included, to be honest), the first sign of what would become known as MLE was the appearance more than a decade ago of Ali G, the comical fictional character created by Sacha Baron Cohen. A distinctive part of Ali G’s accent was his high-frequency [s] and [z], as in the following “I is in South Central LA”:

And here is some speech by a real MLE speaker, earlier this year. Again, we hear distinctively high-frequency [s] and [z] (“if another person comes to their post code, or they’re seeing other people in these areas”):

In these hi-f sibilants, the hissing noise is concentrated at higher acoustic frequencies than in plain [s] and [z]. To articulate the hi-f sounds, I place my tongue blade nearer the teeth than in the plain sounds (tongue tip down in both kinds), bringing my lower jaw slightly forward so that the upper and lower incisors create a continuous vertical barrier to the airflow – in fact I feel that such “meeting incisors” act as something of a visual cue to the hi-f sounds. I don’t believe there’s an accepted transcription for them, but [s̟] and [z̟] would be reasonable.

Perhaps the most famous association of hi-f [s] and [z] in English is with heightened or stereotypical “femininity”. Some gay men use these sounds; here is Harry Derbidge from the currently popular TV show The Only Way is Essex, saying “In Essex it’s, I’d say it is pretty easy”:

(It’s worth pointing out that the heightened or stereotypical “femininity” of these sounds also applies to the speech of females. Again from The Only Way is Essex, the model and beautician Amy Childs would be an example of a female speaker with higher-than-average frequency [s] and [z].)

To my ear, French is a hi-f language. Many (though not all) French speakers use hi-f [s] and [z] without any “feminine” connotation. In this interview with French President Sarkozy, the first interviewer clearly has hi-f sibilants. Sarkozy’s [s] and [z] are generally less hi-f, but for example his emphatic savez-vous at 0:17 begins with an [s] which is decidedly hi-f by cross-linguistic standards:

There are also at least two kinds of low-frequency [s] and [z]. One is the apical variety, made with a raised tongue tip, which is heard in languages including Spanish, Greek and Icelandic; apical [s̺] also appears in Irish English, as a product of t-weakening. Another low-frequency variety is posterior-laminal, made with a part of the tongue just behind the main blade area; it is heard in Dutch and in Scouse (Merseyside English).

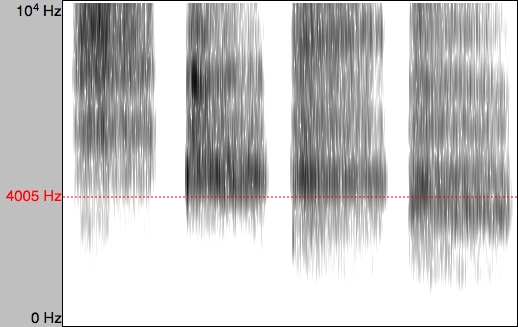

Here are spectrograms and an audio clip of me producing (1) hi-f [s], (2) plain [s], (3) posterior-laminal [s], (4) apical [s̺]:

Returning to MLE, we know that it has diverse sources, including Caribbean English and traditional Cockney; it also has its own innovations. So what of its hi-f [s] and [z]? Can we say where they’ve come from?

In his talk Paul Kerswill refers to music and youth culture:

people from the Caribbean were the first post-war migrants [to London]… post-war we also have the growth of music, something called separate youth culture… it probably started in America… it’s probably no surprise in fact that even though the West Indians, the Caribbeans, are not the largest ethnic minority any more, their music certainly sets the tone.

I suspect that the source of MLE hi-f sibilants was African American hip hop culture. I’m no authority on this, but the sibilants in this early example sound hi-f to me:

Long before I became fully aware of MLE, I’d been struck by Eminem’s clearly hi-f [s] and [z] in his rapping, despite his use of plain [s] and [z] in his interview speech. It struck me particularly because the long-standing association of hi-f [s] and [z] with “femininity” in the anglophone world seemed somewhat at odds with the machismo of rap culture.

Recall that MLE preserves [h], so that today’s real Eastenders are no longer h-droppers. This overturns one of the great acknowledged symbols of working class speech in London (and beyond). The use of hi-f sibilants in MLE – perhaps like the rise of earrings for men in the 70s and 80s – seems to overturn another kind of symbol.

I think that English people become programmed to pay close attention to vowels rather than consonants, as vowels are more likely to indicate where a person comes from. I had not noticed this trend before reading your post.

In the second sound file, he doesn’t say “they see another people in these areas” he says “they’re seeing other people in these areas”.

I think you’re right. Thanks

Hi-f [s] and [z] are definitely easier to pronounce at the teeth, but ever since I was a child I think I’ve been pronouncing a really sharp *apico-alveolar* [s] by making the groove extremely concentrated.

Here’s a recording of me pronouncing some pseudo-Mandarin syllables with this [s]: https:/ /paste.c-net. org/LangleyAitoro

What surprised me when I looked at its spectrogram is that it’s not hi-f in the way shown by the image in your post, but in that it has two discrete frequency islands with concentrated energy, the lower one varying between (3-6 kHz) and (4-6 kHz) in its boundary but the other shooting well over 7.5 kHz.

This highly grooved [s] isn’t used consistently by my speech in reality, and it seems to me it also really likes to bring in secondary articulation at the back of my mouth, such as velarization or pharyngealization.