Notre Dame: note what it’s not

Every weekday, I tweet a word from the CUBE dictionary (CUrrent British English) which I co-edit. I generally pick something from the news, so this week’s terrible fire made Notre Dame an obvious choice:

Every weekday, I tweet a word from the CUBE dictionary (CUrrent British English) which I co-edit. I generally pick something from the news, so this week’s terrible fire made Notre Dame an obvious choice:

#NotreDame #pronunciation n ɔ́ t r ə d ɑ́ː m • ˌnɒtrəˈdɑːm • NOT-ruh-DAAM https://t.co/iAPAKi7hyC

— CUBEwords (@CUBEwords) April 16, 2019

As you see, the first syllable is shown as containing the short vowel of LOT. (The symbol ɔ is its contemporary value, while the traditional ɒ is now less realistic; for a description of how standard British vowels have shifted, see my English After RP.)

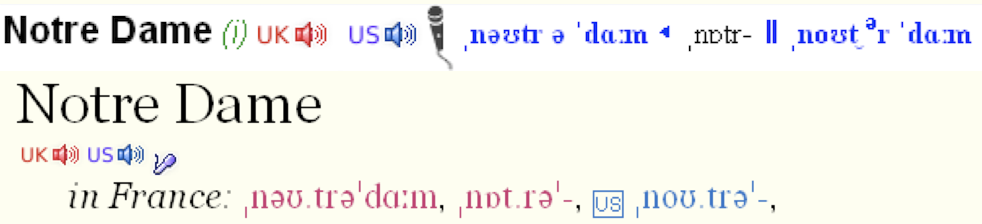

Often I’ll check the CUBE pronunciation against video clips and other dictionaries. In the case of Notre Dame, I was surprised to find the Longman and Cambridge pronunciation dictionaries recommending as their first British choice a different pronunciation, with the long vowel of GOAT in the first syllable:

If any British newsreaders or reporters used such a pronunciation this week, I didn’t hear it. I only heard the LOT vowel, as shown in CUBE and as listed in second position by Longman and Cambridge:

And here are some more examples with LOT from before this week:

Using the GOAT vowel in Notre strikes me as American, not British. Even when referring to the American University of Notre Dame, with the vowel of FACE in Dame, Brits may still use LOT in Notre:

Notre is just one of numerous foreign words in which a stressed ‘o’ is pronounced by SSB speakers with their LOT vowel and by GenAm speakers with their GOAT vowel. Examples include Davos, Sochi, Macron and risotto (I’ve previously blogged about the first two). If you want to go into this in more detail, I wrote a paper thirty years ago which you can find here:

Studies in the Pronunciation of English

First published in 1990, this collection celebrates the life and work of Professor A. C. Gimson, four years after his untimely death in 1985. A. C. Gimson, Professor of Phonetics at University College London, 1966-83, was the most distinguished and influential phonetician of his day concentrating specifically on English speech.

A nice demonstration of the Anglo-American difference is heard at the start of a commercial featuring British chef Gordon Ramsay. You can hear the American risotto with GOAT from an actor imitating Ramsay preposterously, who is interrupted by the real Ramsay saying British risotto with LOT:

So, given that SSB speakers don’t seem to use GOAT in Notre, why would the great Longman and Cambridge dictionaries recommend it? The explanation for this kind of thing is almost always the lingering influence of old RP. My go-to website for old-fashioned RP pronunciations is British Pathé. And there, sure enough, we find Notre Dame with GOAT, e.g. in this 1932 newsreel about the then Crown Prince Of Ethiopia:

I wouldn’t recommend this pronunciation to those aiming at an SSB accent today.

Finally, it’s worth noting another common pronunciation for Notre Dame that isn’t mentioned by Longman or Cambridge (or by CUBE, which only gives one pronunciation per word). This has the short vowel of TRAP in Dame, like dam or damn:

The more I know about pronunciation the more I question how much we should rely on pronunciation dictionaries. Mainly if you are a non native speaker of English. Thank you Geoff for sharing

Thanks for commenting, Stella. I recommend all those I teach to get into the habit of using dictionaries regularly – especially to check familiar words, which may well contain surprises (stress, schwa, /s/ v. /z/, etc.). The major dictionaries are reliable for most vocab; and even though some of the traditional vowel symbols can be misleading, the audio clips are generally pretty contemporary.

As a native speaker of English from the American Midwest, sometimes dictionaries (pronunciation or otherwise) can be a bit annoying when they don’t show the only pronunciation of a word that you’ve ever used or heard your entire life. One example I can think of right now is the name “Aristotle.” I’ve only ever heard that word pronounced with stress on the 3rd (penultimate) syllable [ˌɛrəˈstatl]. But I’ve _never_ seen that pronunciation listed in any dictionary (The stress is my focus here, not the vowel qualities, in case that’s not clear).

I would be OK with a dictionary listing the pronunciation [ˌærɪˈstɒtl]. The stress pattern is mine and my pronunciation can be derived from it. But then there would have to be British people who actually used that pronunciation and I’m not sure if that’s the case.

Sometimes it makes me wonder if lexicographers only pay attention to how Ivy League or Oxbridge “elites” pronounce words and ignore how everyone else speaks. I hate to make accusations like that, but I can’t help but wonder sometimes. It just makes you feel a little excluded sometimes or like the author thought your pronunciation was too stupid to even be worthy of mention, even though everyone you grew up with said the word in exactly the same way as you, whether they were educated or uneducated, teachers or students.

I realize that Stella is a non-native learner of English, so she has different needs and concerns than me, but I’m just offering a different perspective. As a non-native learner, how you pronounce the specific word “Aristotle” probably isn’t that big of a deal in the grand scheme of things. But that was just the example I thought of. There are other words where my pronunciation isn’t listed in any dictionary.

Here are some other examples of my and in this case also my countrymen’s pronunciation of a word not being shown in a dictionary. The following examples are from a pronunciation dictionary I have in front of me right now. Keep in mind that this dictionary is supposed to show both British and American pronunciations:

Bianca (given name) /bi ˈæŋk ə/ (only pronunciation given in dictionary)

Everyone in America says /bi ˈɑ:ŋk ə/. We would never treat a foreign (or foreign-looking) name like that, unless (maybe) it was a very old name in the Anglosphere. N.B. I used /a/ in my previous comments to represent the (stressed) vowel phoneme in “father”, now I’m using /ɑ:/ like the dictionary in front of me does, even though /a/ is probably phonetically more accurate for most Americans (as well as being a familiar, Latin symbol and a symbol that everyone has right on their keyboard).

Bichon (Frise) /ˌbi:ʃ ᵊn ˈfriːz/ (dog breed) (only pronunciation given)

To American ears, the pronunciations /’bi:ʃ ᵊn/ (BEESH-en) and /friːz/ (freeze) sound Anglicized to a comical degree. The vowel in the second syllable of “bichon” can probably be /ɑ/ or /ɔ/ (“ah” or “aw”) in America, but it’s NEVER a reduced vowel. The American pronunciation is /ˈbiː ʃɑ:n friˈzeɪ/. The pronunciation /biː ‘ʃɑ:n friˈzeɪ/ (but /ˈbiː ʃɑ:n/ when not followed by “Frise”*) might be another possibility. The second pronunciation the Wikipedia article gives /ˈbiːʃɒn frɪˈzeɪ/ is acceptable to me, although reducing the unstressed (1st syllable) vowel in “Frise” is ever-so-slightly odd. People often just say /ˈbiː ʃɑ:n/, especially if they own one.

Berˌmuda ˈshorts (only stress pattern given)

In America, we say Berˈmuda shorts (ber MEW da shorts). The stress pattern Berˌmuda ˈshorts (ber mew da SHORTS) reminds me of how British chefs, like Gordon Ramsay above, say the names of sauces. They say lamb ‘SAUCE and the like. Whereas, if we actually had lamb sauce in America we would call it ‘LAMB sauce, with the same stress pattern as ‘LAMB chops or ‘HOT sauce.

Those were just some examples I found on a few pages in the B section of the dictionary.

* i.e., shifting stress in “Bichon” depending on whether it is or isn’t followed by “Frise”

If you haven’t already seen it, you may enjoy the end of this post, where Neil Sedaka rhymes Bianca and conquer.

For a second I was scared you were going to write that Americans pronounce the cathedral in Paris as [noʊɾɚ ˈdeɪm]. Normal Americans actually make a distinction between the cathedral in Paris [ˌnoʊtrə ˈdam] and the Catholic university in Indiana [ˌnoʊɾɚ ˈdeɪm]. It’s always important to keep in mind that the way an American pronounces the name of a long-established, thoroughly American place in the middle of America often tells one nothing about how they will pronounce the name of a foreign place with the same name (which may or may not be its namesake). For example, I’m American and I say: [ˈlaɪmə], Ohio (etc.), but [ˈlimə], Peru; [ˈkeɪroʊ], Illinois, but [ˈkaɪroʊ], Egypt; [marˈseɪlz], Illinois, but [marˈseɪ], France; [vɚˈseɪlz], Indiana, but [vɚ-] or even [vɛrˈsaɪ] in France; [səˈlaɪdə], Colorado, but [saˈliða] (“exit” in Spanish). For those who don’t know the IPA, the places I referred to above were Lima, Cairo, Marseille(s), Versailles and Salida.

It’s nice to see you back, by the way. I followed this blog years ago.

Thanks, Rick. Aside from the well-known Dame difference, how consistent would you say most Americans are about [trə] for Notre in Paris and [ɾɚ] for Notre in Indiana?

I remember being surprised that Pierre, SD is pronounced like peer/pier. And how about Beaulieu in England – ˈbjʉwlɪj.

Geoff, my RSS reader announced that you had posted a new article about intonation and Meghan Markle, but it says “Protected” and when I follow the link I get a 404 not found page. Did you mean to post it?