British English just got more American

When I was a child I noticed that the Americans I heard on TV could do something with just, already and yet that I couldn’t. They could use these words with the plain past tense, whereas I had to use the have-perfect:

When I was a child I noticed that the Americans I heard on TV could do something with just, already and yet that I couldn’t. They could use these words with the plain past tense, whereas I had to use the have-perfect:

Me: I’ve already eaten.

Me: Have you eaten yet?

Americans: I already ate. (Or I ate already.)

Americans: Did you eat yet?

Just, already and yet refer to the recent past in a way that’s relevant to the present. My British grammar insists on the have-perfect for this kind of meaning, with or without just, already or yet. The plain past, in my grammar, is for past events without present relevance; so I ate and I didn’t eat tell you about my eating in the past but nothing about my present eating situation.

American English can use either the have-perfect or the plain past for the present-relevant meaning. Listen to this headline from today’s news on the American CNBC network:

In my native grammar, that sentence belongs in a documentary, not in a news headline. It tells me about something that happened in the past; someone else may have become Ukrainian prime minister since. But CNBC was telling me about something very recent that’s still relevant now. My equivalent would be The chairman of the Ukrainian parliament has been elected prime minister.

Present-relevant use of the plain past has recently become very fashionable in British English – via the ‘Trojan horse’ of the American-style advertising slogan which tells us that something just got better, or just got more something: This figure of speech is everywhere. Here it is promoting eBay and the British loyalty card Nectar:

This figure of speech is everywhere. Here it is promoting eBay and the British loyalty card Nectar:![]() Thomson holidays even use the term in a URL:

Thomson holidays even use the term in a URL: It’s used not only in advertising but in headlines:

It’s used not only in advertising but in headlines: Even from posh old Country Life (which has been guest-edited by Prince Charles):

Even from posh old Country Life (which has been guest-edited by Prince Charles): And from the government:

And from the government: But it isn’t just a matter of things getting better, easier, higher and sexier. British headlines now often use just with the plain past to report events:

But it isn’t just a matter of things getting better, easier, higher and sexier. British headlines now often use just with the plain past to report events:

Precedents for this kind of thing are all over the internet. We Brits are constantly exposed to updates of various kinds expressed with the plain past of American English. Many are news items from the US:

Precedents for this kind of thing are all over the internet. We Brits are constantly exposed to updates of various kinds expressed with the plain past of American English. Many are news items from the US: But many instances concern the here and now of our own lives. Software updates are announced like this:

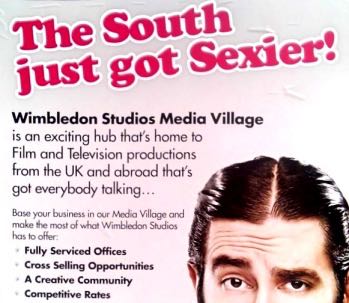

But many instances concern the here and now of our own lives. Software updates are announced like this:![]() In my native English, this would be has been successfully updated. When I log on to Twitter, I get messages like this:

In my native English, this would be has been successfully updated. When I log on to Twitter, I get messages like this: This plain followed triggers in my mind questions like When were they following me? and When did they stop following me? Of course Twitter’s intended meaning is that these people recently decided to follow me and are still following me now: in my native grammar, they have followed me. Thanks to the internet, Britons are exposed constantly to American grammar in a way that is much more personal, much less distant, than the American TV on which I was raised. In my childhood, American English came from far away and sounded glamorously alien. But young Brits today have no idea that their social media announcements were written by Americans. It’s just part of their life.

This plain followed triggers in my mind questions like When were they following me? and When did they stop following me? Of course Twitter’s intended meaning is that these people recently decided to follow me and are still following me now: in my native grammar, they have followed me. Thanks to the internet, Britons are exposed constantly to American grammar in a way that is much more personal, much less distant, than the American TV on which I was raised. In my childhood, American English came from far away and sounded glamorously alien. But young Brits today have no idea that their social media announcements were written by Americans. It’s just part of their life.

Overall, British usage of the plain past and the have-perfect remains different from American usage. This Google Ngram shows that while just saw remains far less common than have just seen in British books (eng_gb), the former has overtaken the latter in American books (eng_us):

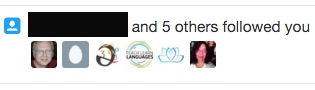

Such Ngrams tell us about published books, where grammar is probably more conservative. In speech and online chat, things have probably changed further. I hope John Wells won’t mind me sharing a social media moment: John’s reply to my query was ‘Probably not’. It wouldn’t surprise me if I’ve used plain past with just myself on this very site without even noticing that my grammar’s shifting.

John’s reply to my query was ‘Probably not’. It wouldn’t surprise me if I’ve used plain past with just myself on this very site without even noticing that my grammar’s shifting.

I first planned to write this post years ago. I took the Wimbledon Studios photo above at the time: it’s dated March 2012. My title was originally going to be Did British English just get more American? That title had an irony which seems to have faded over the intervening years. I’ve changed the title from a question to a statement: in 2016 I suspect some younger British readers will find nothing grammatically remarkable in the sentence British English just got more American.