The demise of happY laxing

One of the distinctive things about Received Pronunciation was its various uses of the lax vowel quality ɪ. Aside from the KIT lexical set, it occurred in three positions:

One of the distinctive things about Received Pronunciation was its various uses of the lax vowel quality ɪ. Aside from the KIT lexical set, it occurred in three positions:

1. Finally unstressed, ie the happY lexical set: happy, coffee, chimney, etc

2. The start-point of the NEAR diphthong ɪə: near, beer, diarrhoea, etc

3. The end-point of the front-closing diphthongs FACE, PRICE and CHOICE: feɪs, praɪs, tʃɔɪs, etc

The obsolescence of lax happY in standard BrE has been widely described (not forgetting, of course, that lax happY survives happɪlɪ in some broad regional accents). Here’s the word solidity from a 1947 Pathé newsreel, ending in tɪ, and from the contemporary Cambridge online dictionary, ending with the FLEECE vowel, tɪj:

But the happY set was not the only position in which lax ɪ fell increasingly out of use in the standard accent. The same thing happened at the same time to the NEAR diphthong. NEAR words increasingly began with a long-tense FLEECE-type quality rather than a short-lax KIT-type quality, as I illustrated in an earlier post with the word beer, from a 1930s Pathé film and the contemporary Cambridge online dictionary (note also the brevity of the lax ɪ start-point in the old diphthong):

In the front-closing diphthongs too, RP’s specification of a lax final element seems not to have endured. The end-point of FACE, PRICE, CHOICE is still variable, including non-high, non-close values such as ɪ and e. But this can be seen as phonetic undershoot, a natural failure to move fully in the direction of i/j. The essence of such diphthongs is movement in that direction, rather than the maximal achievement of a target. What distinguished RP was its use of a lax quality as a maximal target, even in strongly articulated forms where speakers today would go further. Compare RP bɔɪ with a contemporary boy boj from the Cambridge online dictionary:

(Note also the creak, or vocal fry, which was a feature of male speech in RP. Today it’s more a feature of younger, female speech.)

One of the problems with insisting on ɪ as the end-point of front-closing diphthongs is that it precludes front-closing diphthongs which have ɪ as the start-point. This is wrong, counter-evidence being the standard BrE FLEECE vowel, which is phonetically ɪj or ɪi̯. As John Wells wrote of FLEECE in his Accents of English:

the general phonetic nature of this vowel could be adequately represented as /i/, as /iː/, or indeed as /ɪi/, /ɪj/ (p. 140)

In RP Smoothing can also apply to /iː/ and /uː/… This can be interpreted as evidence in favour of analysing FLEECE and GOOSE as underlyingly diphthongal, /ɪi, ʊu/ (p. 240)

Phonologically, FLEECE has the same end-point as FACE, PRICE and CHOICE. Insisting on ɪ as the end-point of the latter three effectively makes the false claim that languages can make a distinction between diphthongs which end in ɪ and diphthongs which end in i̯/j.

So how did this extensive and distinctive use of lax ɪ in RP arise? In Accents of English (p. 212) John Wells suggested that the laxing of the first element in the NEAR diphthong was a “British prestige innovation”, one of a set of innovations which came to characterize the elite accent RP. I suspect that this may have been true of all three RP uses of lax ɪ described above.

Regarding happY, however, John took an RP-centric point of view and stated the question backwards (p. 258): “Where and when the [i] pronunciation arose is not certain. It has probably been in provincial and vulgar speech for centuries.” I suspect that it had been around everywhere. I suspect that it was RP’s lax ɪ which “arose”, and for reasons which John’s quote suggests: as a British prestige innovation, to make speakers sound different from the “provincial and vulgar”.

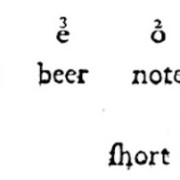

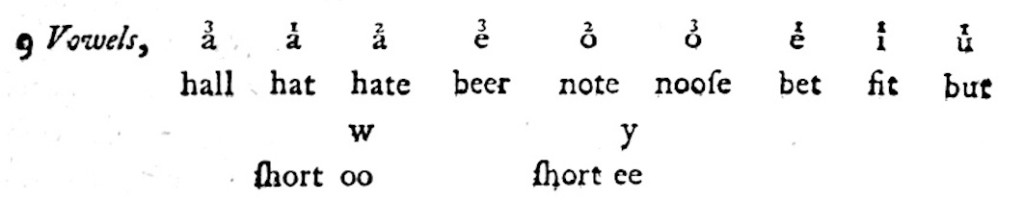

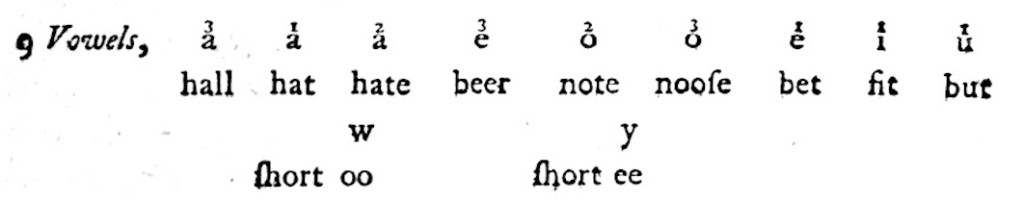

Jack Windsor Lewis wrote a fascinating study which I heartily recommend (bearing in mind that a generation of phonetic change has gone by since it was written). Jack points out that the pre-RP pronouncing dictionaries of Sheridan (1789) and Walker (1791) were “in perfect harmony on recognising the matching of the two vowels not in city but in easy.” According to Walker, “vanity, pleurisy, &c., if sound alone were consulted, might be written vanitee, pleurisee, &c.” Sheridan similarly declared that the sound of y “perceived in the last syllable of lovely, is only the short sound of e in beer”. This is of interest not only because of what it suggests about the pre-RP tenseness of the final vowel in lovely, but also because, as a keyword for the lexical set which Wells would later call FLEECE, Sheridan chose none other than beer:

So RP i-laxing may well have been something which arose in the 19th century; and it started to fade again around the middle of the 20th. (CLOTH-broadening was another RP fashion that came and went in southern Britain.) But before i-laxing had gone out of vogue it was incorporated by A. C. Gimson into his broad transcription system for BrE; and this became fossilized in the 1980s. For the happY set, of course, many dictionaries adopted a new symbol ‘i’, as an abbreviation that stood for both the new standard happY=FLEECE as well as the old happY=KIT. However lax happɪ lives on in the old-fashioned Collins online dictionary; check out for example the transcriptions of easy and divinity. Collins have even managed to get some of their speakers to pronounce words this way, for example chimney:

So RP i-laxing may well have been something which arose in the 19th century; and it started to fade again around the middle of the 20th. (CLOTH-broadening was another RP fashion that came and went in southern Britain.) But before i-laxing had gone out of vogue it was incorporated by A. C. Gimson into his broad transcription system for BrE; and this became fossilized in the 1980s. For the happY set, of course, many dictionaries adopted a new symbol ‘i’, as an abbreviation that stood for both the new standard happY=FLEECE as well as the old happY=KIT. However lax happɪ lives on in the old-fashioned Collins online dictionary; check out for example the transcriptions of easy and divinity. Collins have even managed to get some of their speakers to pronounce words this way, for example chimney:

which to me sounds like pure Manchester (not that there’s anything wrong with pure Manchester).

Whatever the historical sources were for RP’s distinctive lax ɪ in these three positions, the end result was that in classic RP the tense quality i was restricted to Wells’s FLEECE set. Infants acquiring RP learned to pronounce all other close-front vowels as lax. Today, actors sometimes tell me that they need RP, perhaps for a Noel Coward play. Any actor who wants to assume a genuine, classic RP accent should really master these particular patterns of RP i-laxing.

(More on NEAR in the next post.)