Smoothing, then and now

The description of contemporary SSB (Standard Southern British) does not really require centring diphthongs. In this it’s very different from the earlier prestige accent Received Pronunciation. RP’s system of centring diphthongs, though still promulgated in dictionaries and textbooks, was a transitional phenomenon between the rhotic system which pervaded England until the 18th century, and the more monophthongal system we have in the 21st.

The description of contemporary SSB (Standard Southern British) does not really require centring diphthongs. In this it’s very different from the earlier prestige accent Received Pronunciation. RP’s system of centring diphthongs, though still promulgated in dictionaries and textbooks, was a transitional phenomenon between the rhotic system which pervaded England until the 18th century, and the more monophthongal system we have in the 21st.

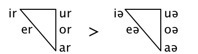

The source of the centring diphthongs (diphthongs ending in schwa) was the vocalization of r when not before a vowel, simplistically as follows: The monophthongization of the resultant centring diphthongs spread first up the back vowels and then up the front vowels. (Splitting the diphthongs into 2-syllable sequences was an alternative fate for uə and iə.)

The monophthongization of the resultant centring diphthongs spread first up the back vowels and then up the front vowels. (Splitting the diphthongs into 2-syllable sequences was an alternative fate for uə and iə.)

A dynamic demonstration of the difference between RP’s centring nature and the system of today is provided by an optional speech process known as smoothing. This affects certain long vowels when they occur before a schwa in the next syllable. The 2-syllable sequence may optionally be smoothed into a single (1-syllable) long vowel.

Smoothing has been around for a long time, but contemporary smoothing works differently from the smoothing of old RP. The older smoothing was described by John Wells as follows:

A long vowel or diphthong changes: iː becomes ɪ, uː becomes ʊ, and a diphthong loses its second element, so that aɪ and aʊ become a.

(Longman Pronunciation Dictionary, 3rd ed., p. 173)

Note that in this older smoothing, the following schwa was unaffected, so that the process had the effect of adding even more centring diphthongs to RP, even reinstating historically lost ones:

iː + ə → ɪə

eɪ + ə → eə

aɪ + ə → aə

ɔɪ + ə → ɔə

uː + ə → ʊə

ɑʊ + ə → ɑə

and

əʊ + ə → əə (not actually a diphthong)

So fire faɪə could become faə and power pɑʊə could become pɑə, etc. The prevalence of centring diphthongs in RP was one the features that gave the accent its distinctive flavour – a flavour perceived as old-fashioned today. Here from an old Pathé newsreel is an assortment of old-fashioned centring diphthongs – “they find th[eə] way… t[ʊə]ring the beautiful countryside… natural p[ɑə]… produced ent[aə]ly with the aid of automatic machines”:

The newer smoothing is simpler: treating contemporary FLEECE and GOOSE as diphthongs, we can just say that the process applies to diphthongs. The output of the (still optional) process is a long monophthong:

ɪj + ə → ɪː

ɛj + ə → ɛː

ɑj + ə → ɑː

oj + ə → oː

ʉw + ə → ʉː

aw + ə → aː

əw + ə → əː

Let’s listen to some examples. First, opera singer Simon Keenlyside, smoothing variety from var[ɑjə]ty to var[ɑː]ty, which could rhyme with party:

Here a TV interviewee smooths liabilities from l[ɑjə]bilities to l[ɑː]bilities:

To demonstrate the monophthongal nature of the smoothing, here is the speaker’s smoothed ɑjə edited before –st, which gives a pretty natural-sounding last lɑːst:

(This also supports the analysis of the contemporary PRICE vowel as ɑj, with a first element identical in quality to PALM/START.)

Now let’s look at the MOUTH diphthong aw followed by schwa. Here is chef Sam Clark saying sourdough with an unsmoothed awə in sour:

Nicely demonstrating the optionality of smoothing, he also produces the word in a smoothed version with saː in sour:

The first part of this word sounds like a longish pronunciation of the word sad:

which supports the analysis of the MOUTH diphthong as beginning with the same quality as the TRAP vowel, a.

Next, the FACE diphthong ɛj followed by schwa. Here is UCL’s Prof. Mark Miodownik saying thinner layers with an unsmoothed sequence ɛjə in layers:

Whereas here he produces layer smoothed to lɛː (like lair) in an atomic layer of graphene:

When the GOAT diphthong is immediately followed by schwa, there is no difference between the effects of old RP smoothing and those of the newer kind. Since GOAT begins with schwa, the result either way is a long schwa, ie the NURSE vowel. Here is RP speaker John Wells saying lowered with a smoothed əː vowel:

Words in the NEAR set are often pronounced as sequences of FLEECE + schwa. FLEECE itself is a narrow diphthong ɪj, so that near may be pronounced nɪjə. When this undergoes contemporary smoothing, it produces a long version of the first element, ɪː. The hɪjə pronunciation of here can be heard from Prof Mark Miodownik saying here a carbon fibre composite is being made:

And this is BBC presenter Andrew Plant saying all these Christmas cards here, with the smooth hɪː pronunciation:

(Many younger speakers produce NEAR words generally in the smooth ɪː form.)

Contemporary smoothing is particularly common immediately before r or dark l. Above we heard Mark Miodownik smoothing layer in layer‿of. Here is Prof. Jim Al-Khalili saying curious and inquiring mind, with smoothing of inqu/ɑjə/ring to inqu/ɑː/ring:

Turning to cases with dark l, I’ll and aisle may be pronounced ɑjəl, where ‘pre-L breaking’ adds schwa between the diphthong and dark l; and this can be smoothed to ɑːl. Prince Harry does exactly this in “he’s going to walk down that aisle with his future wife”:

Similarly, Royal Mail may be pronounced rojəl mɛjəl, but is smoothed here by telecoms honcho Richard Hooper to roːl mɛːl:

I’ll end with GOOSE + schwa. The Oxford Advanced online dictionary’s audio pronunciation of secure is unsmoothed sɪkjʉwə. On the other hand, the audio for security exhibits contemporary smoothing, sɪkjʉːrɪtɪj, with ʉwə smoothed to ʉː before r:

Of course the dictionary sticks to the old-fashioned transcription /ʊə/ in both words, /sɪkjʊə/ and /sɪkjʊərɪti/. This transcription reflects neither of the actual pronunciations. Furthermore, the old account of smoothing as stated by John Wells has nothing to say about why the two words should exhibit this pronunciation difference, since old smoothing didn’t even apply to /ʊə/.