Britney, Pitney and vocal fry

A phonetic drama unfolded during December when a recent article from the Journal of Voice was sexed up by Science Now (“UP TO THE MINUTE NEWS FROM SCIENCE”):

A phonetic drama unfolded during December when a recent article from the Journal of Voice was sexed up by Science Now (“UP TO THE MINUTE NEWS FROM SCIENCE”):

A curious vocal pattern has crept into the speech of young adult women who speak American English: low, creaky vibrations, also called vocal fry. Pop singers, such as Britney Spears, slip vocal fry into their music as a way to reach low notes and add style. Now, a new study of young women in New York state shows that the same guttural vibration—once considered a speech disorder—has become a language fad… Historically, continual use of vocal fry was classified as part of a voice disorder that was believed to lead to vocal cord damage.

In short, Britney is a danger to your daughters’ throats. Britain’s Daily Mail eagerly took the take-home message home:

There is a danger in speaking like this… the speech habit can cause contact granulomas… painful lesions on the vocal cords…

Fortunately there was a response of measured objectivity in a post on Language Log by leading phonetician Mark Liberman. His main complaint was against the alleged novelty (and sex-specificity) of the phenomenon – “creeping in” or “still here”? – and he sensibly called for real quantitative analysis:

The research… doesn’t raise the issue of changes over time, or even of differences between males and females… It may well be true that there’s cultural variation in the prevalence of vocal fry… There’s plenty of evidence out there to look at, in the form of recordings across time and space, and I look forward to seeing the results when they emerge… It’s too bad, though, that Science Now wrote the story as if this research had already been done!

Liberman’s post (including its Update) is valuable, but it skims over a mixture of issues that I think we can usefully disentangle:

(1) Is or was vocal fry used more by some groups of speakers than by others, and if so, which groups?

(2) Where use of vocal fry is more extensive, is it phonologically indiscriminate or conditioned?

(3) Does vocal fry carry any cultural or other connotations?

(4) Is vocal fry distinct from other kinds of irregular phonation?

(5) Is the use of vocal fry in speech distinct from its use in singing?

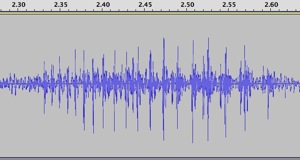

As a preliminary, let’s clarify what we’re talking about. “Vocal fry” is a term widely used in the USA for very low frequency voicing – the vocal cords vibrating far less often per second than in normal voice. Such voicing is often (but not always) irregular, with successive vibrations differing in duration and/or size. Brits more commonly use the term “creaky voice”. “Fry” vividly describes the irregular variety (like the bubbling of a frying pan), while “creak” evokes the more regular kind, which resembles the sound of an unoiled door-hinge. But the regular and irregular kinds seem never to be systematically differentiated in language. Here are waveforms and clips of the relatively regular and irregular kinds, respectively:

To address my issues (1) and (2), I think we can identify various degrees of vocal fry use in English:

First degree: occasional/optional use of vocal fry in stretches of utterances where the default is low-pitched normal voicing.

Second degree: common/default use of vocal fry for those stretches of utterances which are phonologically low.

Third degree: more extensive use of vocal fry to include e.g. phonologically high accents.

I’d say that the first degree of vocal fry is the universal default. In other words, I’d expect that in most speech communities of the world, some speakers sometimes use vocal fry where low-pitched normal voicing is the usual thing. I don’t think the first degree ever catches anyone’s attention.

It’s the second degree that sticks out more. It used to be said (e.g. when I was an undergraduate at University College London in the late 70s) that creak was common at the ends of intonational falls produced by male speakers of RP (Received Pronunciation). Here’s a classic of the kind (Pathé newsreel, 1932):

This gentleman produces two intonational falls, on Road and May, but only creaks at the end of the second (pre-pausal) one. Some RP males were more consistent in using fry on phonologically low material. The English film star George Sanders, who played suave bounders in Hollywood and voiced the tiger Shere Khan in Disney’s Jungle Book, turned male-RP creak into a trade mark:

(The regular and irregular clips above were from Sanders’ Khan and play respectively.)

This kind of male British creak could still sound up-to-date in the swinging sixties:

An American contemporary of Sanders with characteristic fry-termination was Hollywood sex symbol Mae West. Liberman gives this clip of her famous “Why don’t you come up some time and see me?”:

So Liberman is certainly right to suspect that vocal fry is not a recent invention. But second degree fry has not been consistent over time. The male-RP pattern now seems extremely old-fashioned; Science Now is decades out of date when it claims (my emphasis)

anecdotal reports suggest that the behavior is much more common in women. (In British English, the pattern is the opposite.)

In part, I’m persuaded that American fry has genuinely increased precisely because this hasn’t happened to anything like the same extent in Britain. I don’t have stats, but from a London perspective the prevalence of creak among American students and tourists is pretty distinctive. Then there’s the media. Here’s an ad for Airbnb:

This actress, like George Sanders, is clearly using vocal fry as her default for post-fall intonation (what the traditional British analysis calls “low tails”). I doubt that you’ll find many American ads from twenty or even ten years ago with second degree vocal fry like this. And you’d have to search a long time to find a British advertisement with the same phenomenon, though admittedly there are signs that the newer American fry is developing a British counterpart: here is Emma Watson (Hermione in the Harry Potter films) saying to antagonise her:

What of third degree vocal fry? The extreme case would be something like “Tony”, the imaginary friend who possesses the boy Danny in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980):

In more natural speech, at least some younger Americans, at least some of the time, use creak not only on intonational tails but also on phonologically high accents. I just stumbled on this from a male teenager on YouTube:

And about ten years ago in a Vermont ski resort, I found myself on a long cable car ride with two male snowboarders whose entire conversation, I swear, was in vocal fry. Which suggests that Science Now is not quite “UP TO THE MINUTE” on the story of increasing American fry, nor on the mark about sex differences.

So – moving on to issue (3) – if vocal fry is not just a universal constant, but rather is used more extensively by some groups and at some times, what does it connote? Is it just an arbitrary indexical marker of these groups, or is there some overall sound-symbolic association?

Liberman cites some research on Chicana/o English which suggests that the “meaning” of vocal fry may be very unclear. But I think some generalizations can be made. People naturally creak when they’re physiologically very relaxed, for example when sliding towards or out of sleep. Of course the semiotics of “relaxation” will be highly context dependent. When Mae West’s speech signalled a “relaxed” attitude in sexual allusions, many were shocked in an era that was very unrelaxed about sex. George Sanders’ characters are typically ominous, but they threaten in a “relaxed” manner – as if malfeasance is routine to them – which is all the more sinister. I don’t know any Chicano gangsters as mentioned by Liberman, but it wouldn’t surprise me to find them using the George Sanders trick.

In The phonetic description of voice quality (1980) John Laver says that extensive vocal fry “signals bored resignation”, but again we have to take context into account. If a speaker is simultaneously signalling engagement, then the “relaxation” of vocal fry can suggest “knowingness”. I think this is characteristic of the Airbnb ad, and of the YouTube teen telling us we’d be better off listening to the song.

The “relaxed-knowing” connotation of fry-termination makes it the converse of Uptalk, which connotes a need to know – specifically, to know that the hearer is following the speaker. If the Airbnb actress switched her creaky tails into Uptalk, she would seem far less knowing and far less sure of herself, which is exactly why we don’t get much Uptalk from the narrators of commercials. But this kind of sound-symbolism is a meta-phenomenon: for some speakers, vocal fry and/or Uptalk clearly become neutral defaults. I’ve certainly overheard more than one person (American, youngish) whose speech used two main terminations: Uptalk non-finally, vocal fry finally. This is the kind of pattern:

Liberman’s tentative illustration of the Chicano voice quality comes from Cheech Marin’s Born in East LA:

Liberman is surely right to suspect that this is not canonical creak. Rather – this is my issue (4) – it’s the so-called “vocal growl” used by Louis Armstrong, Fozzie Bear and death metal vocalists, and it involves the epiglottis and/or the false vocal folds:

We can clearly see the differences between vocal fry and ventricular/epiglottal growl in a magnificent video of the Australian “vocal adventurer” Mal Webb undergoing nasendoscopic (and partly stroboscopic) laryngoscopy as he demonstrates a variety of phonation types. I don’t know whether Cheech’s use of vocal growl in speech is a Chicano thing, but his sung growl obviously resembles Bruce Springsteen’s rough phonation in the original Born in the USA which Cheech is referencing. Growl differs from fry both articulatorily (it’s usually effortful) and semiotically (it clearly doesn’t signal relaxation).

Singing finally brings us to issue (5) – is speakers’ fry distinct from singers’ fry? – and to the original scapegoat, Britney Spears. The Daily Mail article helpfully links to the incriminating video of …Baby One More Time:

It’s clear that most of the creak in this song doesn’t even count as second degree speech fry. Most the time Britney is simply using the long-established pop singer’s trick of beginning phrases with vocal fry. Here’s Bono:

And we can certainly disregard’s Science Now‘s claim that “singers, such as Britney Spears, slip vocal fry into their music as a way to reach low notes”. In the following clip, Britney creaks on the opening syllable I, which is set musically to the note C, then she comfortably sings the E-flat a major sixth lower on the final melismatic syllable go:

So creaky speech and this kind of singer’s fry are basically different. Spoken fry is chiefly associated with endings, specifically those following intonational falls. Singers’ fry is chiefly associated with beginnings, as the singers “find” their initial pitch. The endings of sung phrases, by contrast, are typically sustained and not liable to creak.

However, some singers go considerably beyond this. For my money …Baby One More Time is out-fried by Gene Pitney’s creak anthem, Twenty Four Hours From Tulsa:

As far as I’m aware, this 1963 hit didn’t prompt any scarifying articles about granulomas. Of course Pitney was male, and he wasn’t half-wearing a school uniform. Vocal fry comes and goes, but some people are still bothered by women with… relaxed attitudes.